Resource Center OLLibrary

|

374 |

|

[1898 |

and urged that the whole question should be referred to an

arbitration committee chosen by different nations (§ 374).

This proposal the United States declined to accept. Later, we

raised the wreck of the Maine (1912), and an examination

confirmed the opinion of the court in regard to the mine.

413. The President's Message; the Resolutions

adopted by Congress. In April (1898) President McKinley sent a

special message to Congress. He declared that in the "name of

humanity," in the "name of civilization," and "in behalf of

endangered American interests," the "war in Cuba must stop."

Shortly afterward both Houses of Congress

resolved (April 19, 1898) "that the people of Cuba are, and of

right ought to be, free and independent." Furthermore, Congress

demanded that Spain should give up all sovereignty over Cuba; in

case Spain refused, the President was authorized to use the land

and naval forces of the United States to compel the Spaniards to

leave the island.

Finally, Congress resolved that when peace

should be made in Cuba, we would "leave the government and control

of the island to its people." Later, however, Congress resolved

(1902) that in case of necessity, the Cubans must admit our right

to act as guardians of their liberty (§ 419).

414. We prepare for War with Spain (1898);

the Call for Volunteers; the Call for Money; the Navy; War

declared. Spain refused to grant our demands and we determined

to fight.

The President called for 200,000 volunteers. A

million men stepped forward, saying, "Here am I; take me." Some of

these men had been Union soldiers in the Civil War, while others

had fought on the side of the South; but now they were eager to

stand side by side and fight against Spain.

Furthermore, our people knew that in war money

was as necessary as men; so when the government wished to borrow a

large sum great numbers at once offered to lend it seven times as

much as it asked for. They also declared their willingness to pay

the heavy taxes that would be needed.1

1 The government

asked for a loan of $200,000,000, and raised about $200,000,000

more, every year as long as it was required.

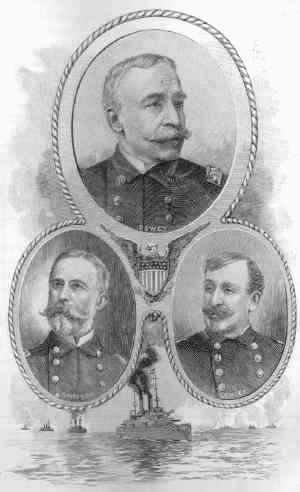

NAVAL COMMANDERS

Dewey

Samson & Schley

|

376 |

|

[1898 |

In a contest with Spain the navy would

naturally take the most prominent part. The President sent Captain

William T. Sampson.1 with a fleet of war ships to

blockade Havana and other ports of Cuba. He also ordered Commodore

W. S. Schley2 to organize a "flying squadron" of fast,

armed steamers to be used as occasion might demand. Congress then

declared war (April 25, 1898).

415. The Battle of Manila. Commodore

George Dewey, who had been with Farragut at the battle of New

Orleans (§ 334), was then in command of our Asiatic squadron

at Hongkong, China. The President ordered him to go to Manila, the

capital of the Philippines (Map, p. 380), and "capture or destroy"

the Spanish squadron which guarded that important port. Our plan

was to attack Spain through her colonies of Cuba and the

Philippines and so strike her two heavy blows at the same time,

one on one side of the world, the other on the other.

Commodore Dewey had only six ships of war. The

Spaniards at Manila held a fortified port; they had twice as many

vessels as Dewey had, but our squadron was superior in size and

armament; last of all, the enemy, though brave men and good

fighters, had never learned how to fire straight.

On May 1, 1898, Commodore Dewey reported that he

had just fought a battle in which he had destroyed every vessel of

the Spanish squadron without losing a man. A French officer, who

witnessed the fight, said that the American fire was "something

awful" for its "accuracy and rapidity."

The "Hero of Manila" was promoted to the rank of

rear admiral; after the war he was made admiral (1899), and

Captain Sampson and Commodore Schley were made rear admirals.

416. Commodore Schley discovers Cervera's

Squadron. Shortly before the battle of Manila Admiral Cervera

left the Cape Verde Islands with a Spanish squadron of seven war

ships. Nobody in America knew whether Cervera was headed for Cuba

or whether he meant to shell the cities on our eastern coast.

1 Captain Sampson had

the rank of Acting Rear Admiral.

2 Schley (sly or schlä)

|

1898] |

|

377 |

|

Commodore Schley set out with his

"flying squadron" (§ 414) to find the enemy. The

Commodore discovered that the Spanish ships had entered

the harbor of Santiago on the southeast coast of Cuba. He

said with a grim smile, "They will never get home." They

never did.

MAP OF CUBA AND NEIGHBORING ISLANDS The entrance to the harbor of

Santiago is long, narrow, and crooked; it was also

protected by land batteries and submarine mines. Our

ships could not get at the enemy. |

|

378 |

|

[1898 |

|

steep heights of El Caney and San Juan, overlooking

the city of Santiago. In spite of defenses made of barbed

wire, they drove the Spanish, with heavy loss, pellmell

into the city. |

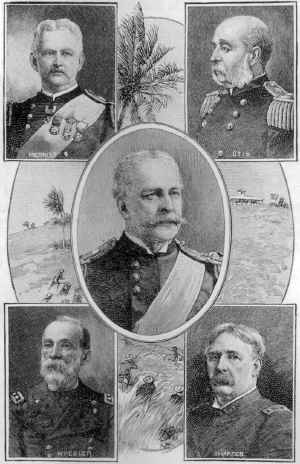

ARMY COMMANDERS

Merritt, Otis,

Miles,

Wheeler & Shafter

Not

long after Captain Sampson left, a great shout went up

from the Brooklyn: "The Spaniards are coming out

of the harbor!" Both sides opened fire at the same moment

(July 3, 1898). But the Spanish Admiral's squadron of six

vessels proved to be no match for our fleet of six

vessels, comprising four powerful battle

ships.1 Such a condition could have but one

result.

Not

long after Captain Sampson left, a great shout went up

from the Brooklyn: "The Spaniards are coming out

of the harbor!" Both sides opened fire at the same moment

(July 3, 1898). But the Spanish Admiral's squadron of six

vessels proved to be no match for our fleet of six

vessels, comprising four powerful battle

ships.1 Such a condition could have but one

result.