of the "Quincy Colony" organized at Quincy, Illinois, June 24, 1854. In September, 1854, the advance guard of the colony came to Bellevue and under the guidance of Logan Fontanelle located a tract of land on the east side of the Elkhorn river, about twelve miles northeast of where Fremont now stands. In the early spring of 1855 the colonists came on. Plans for the future were made. Two miles square were laid off for a townsite and grounds for the coming state capitol and university. The university was chartered by the legislature and school was actually opened in 1858, the Congregational association having taken the institution under its patronage. For a number of years the town and school struggled on, but in 1865 the school building burned and the location of the Union Pacific road a few miles away ended the ambitions of Fontanelle, once a prosperous village of five hundred people, now mostly a cornfield, whose site may be seen by the traveler on the Northwestern railroad up the Elkhorn valley.

Island in Platte River, opposite Old Pawnee Village,

Fremont, Nebraska

|

stolen all the commissary supplies of the expedition from his wagon and the representatives of the Territory of Nebraska were obliged to go hungry. The original receipt for $86.75 expenses of this expedition--on old style blue paper is among the archives of the historical society.

The charters of these concerns is an interesting one for the student of financial experiments. Each bank was authorized to open doors and begin business as soon as half of its initial capital was,--not paid in, but "subscribed." Each bank was authorized to issue its notes and transact a general banking business and "to buy and sell property of all kinds." The charters were to run for twenty-five years and the stockholders were individually liable to redeem the notes issued in gold and silver. In actual practice these acts of incorporation permitted a bank to issue its own paper money notes and to receive deposits without a dollar of capital stock being paid in. The door for unlimited speculation was left open by permitting banks "to buy and sell any kind of property." The stock of the banks was also transferable,--so that the original incorporators might, if they chose, issue the full amount of notes authorized--half a million dollars--and then by transferring the stock to irresponsible parties leave the note holders without recourse. |

Dr. Geo. L. Miller "stock" with beautiful, lithographed certificates which were freely traded for all kinds of property. Settlers from the east came flocking in to enjoy the wonderful prosperity of the frontier. They, too, were soon infected and engaged in the business of buying town lots, staking out additional townsites and projecting new banks. The census taken in October, 1856 found a population of 10,716--more than double what it had been twelve months before. |

people. Some of them are now preserved as relics of past folly. At the very same time the price of town lots and paper pictures representing townsite shares sank out of sight. Misery and despair drove out prosperity and speculation. Everybody was insolvent. Efforts to collect debts were ridiculous. An execution issued against the Bank of Tekamah, which had $90,000 in paper notes outstanding, brought a return from the sheriff that the only property he could find was a ten by twelve board shanty, used as the banking house, and furniture consisting of an old table and broken stove. This bitter experience of territorial Nebraska effectually killed wildcat banking. |

21, in order to transact some business which the Florence "rebellion" had left undone, the distinction between democrats and "black republicans" begins to appear more clearly. Marquette of Cass county and Daily of Nemaha county are the leaders of a little group who are stigmatized in various picturesque frontier phrases as "the nigger party." At this session a liquor license law is passed, repealing the prohibitory law of 1855. Mr. Daily is a leading advocate of the bill and it is reported as part of the republican program to get the German vote. On December 5, 1858, Governor Richardson resigns his office and hastens to Illinois where his friend Douglas is making the fight of his life against Abraham Lincoln for the United States senatorship. The Buchanan administration was opposed to Douglas and Richardson was not willing to hold a Buchanan appointment. The debt to the territory was over $15,000. Territorial warrants were receivable for taxes, but sold for forty-five cents on the dollar. It was the era of "special legislation." When anything was to be done it required an act of the legislature to make a road, building a mill dam--even divorces were granted by the legislature. |

Nebraska. The feud between the North and South Platte section which had raged for several years now reached the white heat of secession. The South Platte people outnumbered the North Platte, but had been out-generaled in every contest. They now resolved to separate from the northern barbarians and unite with Kansas, which was asking admission as a state. New Years Day, 1859, a mass meeting was held at Nebraska City which declared for Kansas. On January 5th a delegate convention from South Platte counties was held at Brownville at which Richardson, Nemaha, Otoe, Clay, Gage and Johnson counties were represented. A memorial to congress was adopted asking that the boundaries of Kansas be changed so as to include the South Platte. A committee composed of E. S. Dundy, of Richardson, R. W. Furnas, of Nemaha, and J. B. Weston, of Gage, was appointed to prepare an address to the people. The movement grew. On May 2 another convention, held at Nebraska City, called an election in all

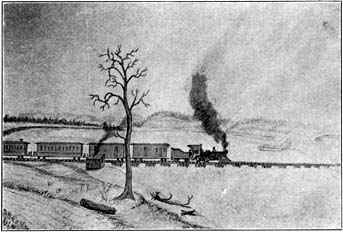

First Temporary Bridge and First Train Crossing the

Missouri at Omaha 1866 the counties south of the Platte to choose delegates to represent them in the coming Kansas constitutional convention to be held at Wyandotte. Members were elected in every county, those from Nemaha county being R. W. Furnas, S. A. Chambers, W. W. Keeling and C. E. L. Holmes. In Otoe county 900 voters out of 1,100 signed a petition to be joined to Kansas. On July 5 the Kansas convention met. The delegates from Nebraska were admitted to seats, but not to vote. A strong party among the Kansas delegates favored annexation of the South Platte region, but there were jealousies and rivalries to overcome. When the test vote was taken on the question, by a vote of 29 to 19, the convention refused to ask the extension of their state to the Platte. The South Platte delegates came home and started an agitation for statehood which resulted in the submission of that proposition the next year. |

|

|

|

|

|

@ 2002 for the NEGenWeb Project by Pam Rietsch, Ted & Carole Miller |

|||