| 298 | NEBRASKA HISTORY MAGAZINE |

they ate their supper sitting on the ground around the fire but they did not want us to do that. The Indian mother would have us sit down on chairs to a table under an arbor. She got a clean tablecloth and napkins and placed on the table silverware and china dishes. At bedtime they invited us to use their log house while they occupied the tepee. The house had a Brussels carpet on the floor and on the wall were enlarged pictures of relatives. There was an organ in the room, a polished stove and a comfortable bed with clean sheets and pillow cases. Next morning their children, a boy and girl, each wearing a school uniform and carrying dinner pails, hied away to school, two miles distant. From a point of observation, I counted fifty or more stacks of wheat ready to be threshed and several herds of cattle belonging to that settlement of Indians.

The North Cheyennes, Rosebud County, Montana.

The Cheyennes were the most cruel of the Indians engaged in the massacre of General Custer and his 260 troopers at the battle of the Little Bighorn, Montana, June 25, 1876. The battle lasted about twenty minutes, and after the massacre the Cheyenne squaws with clubs beat out the brains of the fallen soldiers. The Cheyennes when captured by the government troops were placed on the Reservation, now occupied by them and held as prisoners of war.

It was the latter part of October, 1899, that my daughter and I visited the reservation, then twenty‑four years after the Custer Massacre. The Cheyennes were still held as prisoners of war; I found them sullen and revengeful. Calling at the office of the agent at Lame Deer I was warned to be on the watch as we went among the Indians, that they were very treacherous, and the only protection that would be assured us was not to go beyond the limits of the agency, about two miles square. There were two companies of U. S. troops stationed at the agency.

Starting out in our effort for them, wherever we saw a group of the Indians, old and young, we went, Frances playing on the little organ, the Indians collected around and

NEBRASKA HISTORY MAGAZINE |

299 |

I gave to them Sunday school picture cards and small illustrated papers. The old Indians were just as anxious to receive them as the children. The parents wanted to know what the reading on the cards and papers was about. I had my daughter, then thirteen years of age, read them and I would interpret the same, then I told the parents if they would send their boys and girls to school that they would be able to read nice papers, books, etc., to them.

For two days we worked among the Indians, both inside and outside of the agency lines. In the rounds among them I saw upon their arbors and sheds sabres which they had taken from the bodies of Custer's dead soldiers. Discretion spoke, "See, but not speak." On Sunday our last day there at the time of appointment, we held a meeting in the agency schoolhouse, both the whites and several Indians attended. At the close, a Sunday school was organized and I supplied the same with such helps that were needed.

The Indian Sun Dance.

The next June, returning to the Cheyennes, we camped by the Tongue River, on the east side of the reservation. I saw an Indian tepee and a log house across the river. Visiting the place, I noticed that the inmates were in readiness to leave. On inquiry I learned that they were going to the Shoshones in Wyoming-- 50 miles distance -- to attend a "Sun Dance." Several camps had obtained permission to go. I might explain that the sun dance is a semi‑religious dance (the thought being an atonement for sin) and the act includes great suffering by an innocent person, either a boy or young man, who is willing to be offered or "Lifted Up." At the sun dance a temporary scaffold is erected, built of rough poles fifteen or twenty feet in length, set in the ground to which a cross pole is fastened with rawhide strips. From the cross pole are tied strips of rawhide which hang down nearly to the ground. After fasting for three days and nights the individuals to be offered present themselves to the medicine men who make incisions in their skin and flesh of the breast, back or other parts of their bodies. Through the incisions the medicine men insert strong rawhide tethers and they then are tied to the swinging rawhide strips from the cross pole. Frantic with pain they

| 300 | NEBRASKA HISTORY MAGAZINE |

dance and yell and plunge their bloody bodies trying to break away from the cruel tethers that hold them fast. Finally they are swung up for a period, during the ordeal to test their fortitude and courage, and if in their agony they do not cry to be taken down but brave it through they are released and it is considered that those whom they represented their sins are fully atoned for.

Entering the Indians' log hut, I noticed on the wall, one of the little Sunday school pictures cards that I had handed out to the Indians the fall before. The picture was that of the Crucifixion of Christ and the two thieves on either side. The Indian mother said to me, that she saw and understood why the two thieves were crucified because of their wickedness, but she did not know why the center one (Jesus) should be crucified. (If one will prayerfully wait the opportunity will come when he can present Christ to an inquiring soul.) Before answering her I asked who it was that was going to be offered up at the sun dance for her sins of the past year, she pointed to her son of twelve years; in reply she said that he was a good boy and that she was sorry for him, but she wanted to be forgiven by the Great Spirit.

A Cheyenne Indian Mother.

Then I said to her, that the center one in the picture was God's loving son, who knew no sin, that he was offered up for the sins of the whole world, not only for a year, but for all time, that he was the only one who could atone for sin, and that it was not necessary to go to the Shoshones 150 miles away, but if she would accept his act for her, the Wakan Tanka (Great Spirit) would accept her. Standing silently for a few moments, she said that they would not go to the sun dance, but would accept Christ's atonement for her and her household. Then she insisted that I would go along with her to seven Indian camps who were going also to the sun dance and she wanted me to tell them the same story. I went as she wished and told them about the loving Saviour, and no one went to the sun dance.

Sun Dance. The sun dance was the most important religious ceremony among the plains Indians. It s described minutely by George A. Dorsey, the noted ethnologist, in the Bureau of American Ethnology, bulletin 30. His view has some notable differences from that set forth by Chaplain Frady.

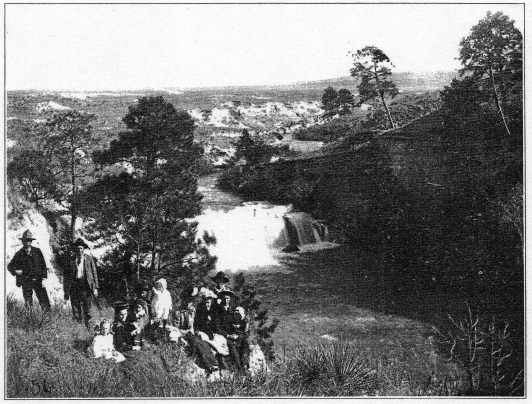

Snake River Falls ‑‑ 36 foot fall.

Amid wildest Nebraska Scenery. Photo 1900.

Butcher Collection in Nebraska State Historical Museum

301

NEBRASKA HISTORY MAGAZINE |

301 |

Motherhood on the Frontier.

At Bonesteel, South Dakota, I made another issue. Late in the afternoon, a lady came to me and said she had just learned that a woman who lived seven miles away was very ill, and that she thought it best for me to go and see her. I went and found the woman in a terrible condition, suffering from the effects of a premature birth, without medical assistance. She was so weakened that she was absolutely unable to help herself in any way. Her three little children, half naked, sat on the dirt floor of the sodhouse crying with hunger. There was nothing to eat in the house either raw or cooked. I did for them all that I could, before returning to town where I got necessary food and clothing from my supplies for the mother and children, then hired a woman to go and take care of them. After making two round trips and late at night, I laid down to rest feeling thankful that it was possible to render timely assistance to her and her three little hungry children.

At Brocksburg, Nebraska, I pitched my Gospel tent and brought up relief supplies. I had the people from far and near gather and we held a three days' meeting. I furnished the food and the ladies cooked it and served everyone. During the meetings sixty persons were brought to Christ and at the close mostly all the converts were baptized.

I mention the foregoing to show that my untiring effort for the drought stricken people was not in vain.

Some of My Travels.

An Indian took it to himself to write a poem of several stanzas, his theme was "The March of Life" and read as follows:

"Go on, go on, go on, go on, Go on, go on, go on, go on."

Thus it was with me in the work, just "Go on," sometimes on foot, on horseback, by wagon and team or by railway and so my roving disposition was largely satisfied. There was hardly a road, a cow‑path or a bridle trail from Sioux City, Iowa, to Hope, Idaho, that I did not travel. I was born on the frontier, reared on the frontier, and knew the

|

© 2004 for the NEGenWeb Project by Ted & Carole Miller |

||