NEGenWeb Project

Resource Center

On-Line Library

| Transportation | 325 |

and Black Hills Railroad, to run its line to "Lost Creek" on the north bank of the Loup River where Oconee now stands. But instead of running the line to Columbus to meet the Union Pacific main line, a bridge spanned the Loup at "Lost Creek" and connection with the main trunk was made at Jackson Junction (now Duncan) eight miles west.

For a while it looked as if Gould's threat to destroy Columbus might become a reality, but on the night of March 19, 1881, the Loup River itself came to the rescue. That night a mighty ice gorge swept the Lost Creek bridge downstream, and railroad officials agreed that, instead of building another bridge, they would run the line down the north side of the Loup. If the city of Columbus agreed to contribute twenty-five thousand dollars toward the expense of laying the line between there and Oconee, Columbus would become the Union Pacific terminal. The bond issue was immediately voted, and within three months the county seat of Platte County was back on the "main line."

Describing the ceremony of opening this all-important section of the road, the local paper announced that free rides to Columbus would be given all those who lived along the branch line. "There will be a grand parade," the accounts continued, "and general carryings-on."

Although the Union Pacific had opened its first freight office in Columbus shortly after the main line reached the town in 1866, little freight was carried in the early years. In the entire month of October, 1866, only thirty-eight thousand pounds of exports or outgoing freight were shipped from Columbus. Two years later, in October, the figures were eighty-two thousand pounds, chiefly flour and potatoes. Seven years later, in October, 1875, the outgoing freight reached a volume of 6,365,000 pounds, over a half million of which was grain.

Third of the big railroad systems to enter Platte County was the Chicago and Northwestern. As in the other cases, a bond issue was floated in the '80's to attract its subsidiary line, the Fremont, Elkhorn and Missouri Valley. The route now includes Creston, Humphrey, Cornlea and Lindsay on its line.

Primarily, however, Columbus has remained a Union Pacific town. In spite of Jay Gould's historic threat and such minor grievances as that described in the early press when "there was great indignation in Columbus and vicinity because the railroad company exacted the fancy sum of ten dollars per vehicle to cross on the U. P. bridge," after the Columbus wagon bridge washed out and the ferry had broken down. Just as the single track poured "life blood" into the little village in the 1880's, so the present railroad continues to be a leader in the economic development of this area.

Rail travel in the early days had its perils also. Mrs. George Parr and Mrs. Ruby Faunce, who made a trip from Utah to Omaha in 1869, rode through Columbus in a box car heated by a wood-burning circular stove. From the windows of their car, they could see Indians on horseback trying to keep up with the train as it made its way across the prairies. In that year the official time card between Omaha and Columbus gave eight hours and fifteen minutes as the traveling time, nine dollars fifteen cents (or ten cents a mile) as the fare.

Coal chutes, a new roundhouse and a stone depot soon were erected by the Union Pacific in Columbus. Repair sheds, blacksmith shops and, in 1910, a one hundred-ton truck scale were added to the railroad's property in town. That same year the old Union Pacific passenger depot burned to the ground, and a further bit of railroad lore was provided in the 1910 account of the two largest locomotives ever to pass through the city. Consigned for the mountainous run of the Southern Pacific line, they were scheduled to make the trip from Philadelphia to Ogden in thirty-five days, and when they arrived in Columbus on January 7 of that year, twenty-five days had been consumed.

With the passing of the early railroad era, much of the color of the original West died. That which had lured so many emigrants from foreign countries, namely, cheap land, was no longer to be found. The first act in the development of Platte County had been the overland stage period, when the famous Russell Ranch west of Schuyler, operated by the eccentric Englishman, John Russell, often hosted as many as one hundred travelers in a single night. The second act had been dominated by the railroad. Before the turn of the century, mechanization began to be felt, and the city of Columbus was big enough now to worry about intra-city communication as well as connecting links with other towns.

"We have thoroughly refitted and refurnished the Tatterstall Livery and Sale Stable, and will continue to furnish the traveling public with horses, buggies, and carriages at reasonable rates," announced the partners, Morse and North in Columbus in 1879. Less than ten years later the Columbus Motor Railway Company

| 326 | The History of Platte County Nebraska |

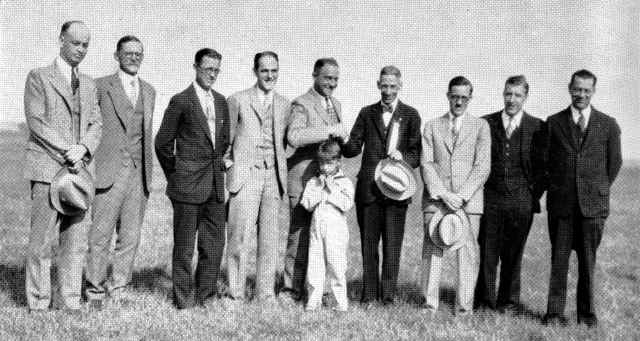

At the Gottberg Airport during the Mid-Nebroska Exposition, in 1929. Left to right: Max Gottberg, Sr., James L. Rich, Fred C. Luchsinger, Harold Kramer, Frederic Kramer (in front), Chamber of Commerce Commissioner Ellis from Omaha, Edward Weaver, Frederick O. Gottschalk, and Doctor Carroll D. Evans, Jr.

took another step toward providing this area with adequate transportation.

Incorporators J. P. Meagher, R. H. Henry, Herman Oehlrich, George Lehman, Leander Gerrard, and John H. Kersenbrock launched the concern.

Articles of incorporation read: "The Columbus Motor Railway Company was formed on May 13, 1887, for the purpose of construction and maintenance of line or lines of Street Railway within the city of Columbus or from the city of Columbus to points within the counties of Platte, Colfax, Butler and Polk. The said railway was to be operated by either steam motor, cable, electricity, or horse power. . .

The next year Thomas McTaggert became the first motorman in Columbus on a street-car line which ran two cars, seating eighteen persons each. Columbus had taken one more step toward urbanization.

With the turn of the century, Platte Valley passed into much the same transportation phase as the rest of rural America. The first automobiles made their appearance. An airplane trip across Nebraska, led by Glenn H. Hastings, appeared in the news of 1910, and was the signal for motor car drivers throughout the state to race the planes. One Omaha automobile dealer even went so far as to challenge Curtis to a contest of speed. There were the usual notices about motor "buggies" climbing hills at the advanced rate of twenty-five miles per hour, and endurance runs were staged by different automobile representatives that reached into other counties and even adjoining states.

Max Gottberg, one of the pioneer transportation leaders in the County, attracted large crowds when he drove a car from his agency up the steps of the Y.M.C.A. building in Columbus; and, also in 1910, a committee of Kearney citizens reported on the experimental "making of some 'oil' pavements" to a committee of equally interested Columbus people.

The Grey Taxi was operated for several years by Clifford Galley and Jay Hensley, with headquarters located in the Weaver Building at 1365 Twenty-fourth Avenue.

The year 1924 saw the first Yellow Cab Company in Columbus. Ted F. Dommann and Elmer and Ollie Miessler were the incorporators of the firm. But it was five years later that Columbus felt the real impact of mobile progress. The Columbus Flying School and the Gottberg Aviation Corporation both were started in 1929; and the Columbus

Daily Telegram of October 10, 1939, carried the following story: "Mrs. Pearl Ruth Dake, daughter of Attorney and Mrs. August Wagner of Columbus, was the

| Transportation | 327 |

first woman to learn to fly in Columbus. Jack Siems, of the Columbus Airport, was her instructor."

Greyhound Bus Depot, 1948. |

Another important factor among the transportation facilities of Platte County is bus service. Besides passengers, both mail and freight are carried by bus. Originally located in the Union Pacific Passenger Depot between Twenty-fifth and Twenty-sixth Avenues on Twelfth Street, the Greyhound bus headquarters expanded until, in 1948, it was located at 2413-17 Fourteenth Street.

When, in 1936, L. E. Minette became the Greyhound bus agent for Columbus, only four bus routes entered the city, bringing a total (for all lines) of just eight buses a day. Today, seven bus lines run into Columbus. They are: the Greyhound Overland Bus, the Burlington Trailways, the Center Service Line, the Beaver Bus Line, the Meridian Transit Line, the Capital Stage Line, and the Blue Star Bus Line. Fifteen Greyhound buses (eight east-bound and seven west-bound) and about the same number of Burlington buses pass through the city every day. The Greyhound Overland Bus Line maintains a service throughout the West from Omaha to the Pacific Coast.

The Burlington Trailways has a service from Omaha to Los Angeles and San Francisco, California. The Center Service Line, known as the Norfolk bus, includes Platte Center, Humphrey, Madison and Norfolk in its itinerary, and makes two round trips daily.

The Beaver Bus Line is routed through Monroe, Genoa, St. Edward, Albion, Elgin and Neligh, where it connects with other east and west-bound buses. This line runs two buses a day.

The Meridian Transit Line runs through Shelby, Osceola and York to Fairmont, where it makes connections with buses that go south through Kansas to Oklahoma City. This line also runs two buses daily.

Union Pacific Railroad Depot of Omaha in 1868 |

The Capital State Line maintains one daily bus service to Lincoln by way of Richland, Schuyler, David City, Seward and Ulysses Corner.

The Blue Star Bus Line is routed through Creston, Leigh, Clarkson, Howells, Dodge, Snyder, Scribner and Fremont, and makes one round trip daily.

In May of 1947, a new intra-city bus line was started by Charles M. Anderson and his wife, Mary Anderson, to give transportation in and around Columbus. So successful was this venture that Mass Transportation, the trade publication of the transit industry, one year later in an article entitled "Personality Plus," rated the Columbus City Lines as one of the outstandingly successful bus operations in cities of comparable size throughout the United States. Outstanding are some of the promotional methods used by the Andersons to make Columbus bus-minded and to describe the owners' package delivery truck line, which also serves fourteen other towns in Platte, Nance, Boon, Madison and Colfax Counties. The truck line was later sold to the Columbus Telegram Company.

| 328 | The History of Platte County Nebraska |

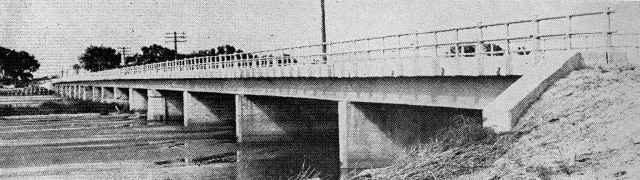

Platte River Bridge, South of Columbus on Highway 91.

Columbus has been the home of many who participated in making transportation history in the building of the West. From Luther North to John T. Cox the roll of honor includes both pioneers and modern railroading men. Cox, who spent forty-four years in the employ of the Burlington Railroad System, resigned in 1925 after acting as traveling freight livestock agent over more than twelve hundred miles of the company's lines.

Another noted figure in the area was Hugh Drake, whose boyhood home was at Humphrey in Platte County. A successful candidate in the primaries for state railway commissioner in 1930, Drake was later appointed chairman of the Nebraska Railway Commission.

Of far more than local significance was the dedication in 1931 of the new Meridian viaduct, which eliminated the only grade crossing in the United States where the Lincoln and Meridian highways crossed railroad tracks at the same point. City and county notables attended the ceremonies at which Carl R. Gray, president of the Union Pacific, was invited to speak.

The viaduct linking the two great transcontinental highways was officially dedicated on the first day of the 1931 Mid-Nebraska exposition, further marking the importance of Columbus and Platte County as a transportation center.

To the people of this region, located as they are in the very heart of the continent, the early wagon trains and keelboats, pack horses, mules --- even the crafts first introduced by the Indians in this area, had a vital significance. Together they constituted a lifeline to the rest of the country, and to other countries. Had the Oregon Trail and the Mormon Trail not passed through the valley of the Platte, it is doubtful whether Columbus ever would have attained its present importance. And, certainly, if the Union Pacific did not service the community with twenty-four trains daily on the main line and four branch lines of its road, the city would present a very different picture of growth. In addition, the Union Pacific brings fifty freight trains a day through Columbus, and freight receipts in 1945 for that town alone show the following figures:

Freight received, $400,540; freight forwarded, $939,000; carloads received, 1,887; carloads forwarded, 3,662. An annual payroll of $513,000 goes to one hundred seventy employees of the Union Pacific who live in the county seat.*

Of prime importance, of course, are the grain shipments which go out from the rich, agricultural Platte Valley farms around Columbus to the markets and ports of the United States and the rest of the world.

Today, the fastest streamlined trains in the world fly along the Platte Valley, crowded with passengers bound for the mountains, the Pacific Coast and other faraway points. As they roll across the prairie, they pass trains loaded with teas, silks, and the handiwork of the people of Japan, India, the Far East. The fruit harvests of California and Oregon go over these rails, and the cattle, sheep and minerals from the rich lodes of the West are shipped through the Platte country in a giant interchange of commerce, made possible by the rails laid through Columbus in the days of the Indian and the buffalo.

*From the Report of 1946.

| © 2005 for the NEGenWeb Project by Ted & Carole Miller |

|||