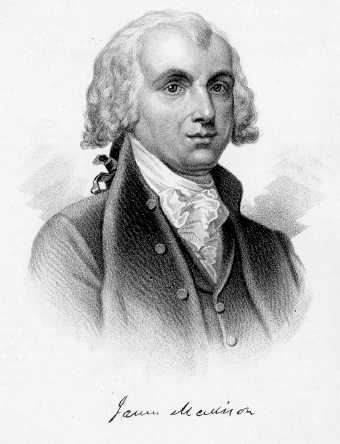

32 JAMES

MADISON.

JAMES

MADISON.

intellectual, social and moral worth, contributed

not a little to his subsequent eminence. In the year

1780, he was elected a member of the Continental

Congress. Here he met the most illustrious men in our

land, and he was immediately assigned to one of the

most conspicuous positions among them.

For three years Mr. Madison

continued in Congress, one of its most active and

influential members. In the year 1784, his term having

expired, he was elected a member of the Virginia

Legislature.

No man felt more deeply than Mr.

Madison the utter inefficiency of the old confederacy,

with no national government, with no power to form

treaties which would be binding, or to enforce law.

There was not any State more prominent than Virginia

in the declaration, that an efficient national

government must be formed. In January, 1786, Mr.

Madison carried a resolution through the General

Assembly of Virginia, inviting the other States to

appoint commissioners to meet in convention at

Annapolis to discuss this subject. Five States only

were represented. The convention, however, issued

another call, drawn up by Mr. Madison, urging all the

States to send their delegates to Philadelphia, in

May, 1787, to draft a Constitution for the United

States, to take the place of that Confederate League.

The delegates met at the time appointed. Every State

but Rhode Island was represented. George Washington

was chosen president of the convention; and the

present Constitution of the United States was then and

there formed. There was, perhaps, no mind and no pen

more active in framing this immortal document than the

mind and the pen of James Madison.

The Constitution, adopted by a vote

81 to 79, was to be presented to the several States

for acceptance. But grave solicitude was felt. Should

it be rejected we should be left but a conglomeration

of independent States, with but little power at home

and little respect abroad. Mr. Madison was selected by

the convention to draw up an address to the people of

the United States, expounding the principles of the

Constitution, and urging its adoption. There was great

opposition to it at first, but it at length triumphed

over all, and went into effect in 1789.

Mr. Madison was elected to the House

of Representatives in the first Congress, and soon

became the avowed leader of the Republican party.

While in New York attending Congress, he met Mrs.

Todd, a young widow of remarkable power of

fascination, whom he married. She was in person and

character queenly, and probably no lady has thus far

occupied so prominent a position in the very peculiar

society which has constituted our republican court as

Mrs. Madison.

Mr. Madison served as Secretary of

State under Jefferson, and at the close of his

administration was chosen President. At this time the

encroachments of England had brought us to the verge

of war.

British orders in council destroyed

our commerce, and our flag was exposed to constant

insult. Mr. Madison was a man of peace. Scholarly in

his taste, retiring in his disposition, war had no

charms for him. But the meekest spirit can be roused.

It makes one's blood boil, even now, to think of an

American ship brought to, upon the ocean, by the guns

of an English cruiser. A young lieutenant steps on

board and orders the crew to be paraded before him.

With great nonchalance he selects any number whom he

may please to designate as British subjects; orders

them down the ship's side into his boat; and places

them on the gundeck of his man-of-war, to fight, by

compulsion, the battles of England. This right of

search and impressment, no efforts of our Government

could induce the British cabinet to relinquish.

On the 18th of June, 1812, President

Madison gave his approval to an act of Congress

declaring war against Great Britain. Notwithstanding

the bitter hostility of the Federal party to the war,

the country in general approved; and Mr. Madison, on

the 4th of March, 1813, was re-elected by a large

majority, and entered upon his second term of office.

This is not the place to describe the various

adventures of this war on the land and on the water.

Our infant navy then laid the foundations of its

renown in grappling with the most formidable power

which ever swept the seas. The contest commenced in

earnest by the appearance of a British fleet, early in

February, 1813, in Chesapeake Bay, declaring nearly

the whole coast of the United States under

blockade.

The Emperor of Russia offered his

services as meditator. America accepted; England

refused. A British force of five thousand men landed

on the banks of the Patuxet River, near its entrance

into Chesapeake Bay, and marched rapidly, by way of

Bladensburg, upon Washington.

The straggling little city of

Washington was thrown into consternation. The cannon

of the brief conflict at Bladensburg echoed through

the streets of the metropolis. The whole population

fled from the city. The President, leaving Mrs.

Madison in the White House, with her carriage drawn up

at the door to await his speedy return, hurried to

meet the officers in a council of war. He met our

troops utterly routed, and he could not go back

without danger of being captured. But few hours

elapsed ere the Presidential Mansion, the Capitol, and

all the public buildings in Washington were in

flames.

The war closed after two years of

fighting, and on Feb. 13, 1815, the treaty of peace

was signed at Ghent.

On the 4th of March, 1817, his

second term of office expired, and he resigned the

Presidential chair to his friend, James Monroe. He

retired to his beautiful home at Montpelier, and there

passed the remainder of his days. On June 28, 1836,

then at the age of 85 years, he fell asleep in death.

Mrs. Madison died July 12, 1849.