50. Great Roman Writers. It would be a great mistake indeed to think of all Romans as cruel or brutal. Among them, even in the days of the empire, were men who had high and noble thoughts.

When Greece was conquered, the best Italians were delighted by the poems and books, the temples and statues, of the subjugated people, and Greek art and learning soon became the fashion. Wealthy Romans took pride in having statues and pictures like those of the Greeks, and every educated Roman studied the Greek language. Books began to be prized.

The books of the Romans did not look very much like ours. They were nothing but long rolls of a kind of paper made from the papyrus plant which grew only in Egypt. This paper was very beautiful, but it was brittle, and the papyrus books that have come down to us are badly cracked and broken. Since the printing press was unknown, the books had to be written by hand. The writing was in black ink and went across the paper in columns. Between the columns were lines in red ink. The books were rolled around sticks with ornamented ends and Soften tied with thongs. Sometimes the rolls had parchment cases or covers of some bright color like yellow or purple.

When a Roman was reading he held the book before him with both hands, slowly rolling up with his left hand what he had already finished and unrolling with his right the part of the book he had not yet seen. When he had finished, the beginning or top of the book would be inside and the end out. So, to prepare the book for the next reader, he had to unwind it all and roll it up the other way.

When a Roman scholar or poet had written a book and wished to publish it, he put it in the hands of the bookseller he had chosen. The bookseller had many skillful clerks whose business it was to make copies. But well trained though they were, they could turn out only pitifully few books as compared with even a hand press to-day. Every copy, moreover, had to be carefully examined lest mistakes be made. In ancient times only the rich, therefore, could afford to own or even see books.

When the copying was done, the Roman bookseller tacked up on his door the name of the book and that of the author. But there were no laws, as there are to-day, to prevent any one from making as many additional copies as he chose. Unless the writer received a gift from some wealthy person he had mentioned in his book  he seems to have gained nothing but honor from the whole proceeding.

he seems to have gained nothing but honor from the whole proceeding.

In matters of daily business the Romans did not usually write with ink on paper. Instead, they used tablets made of wood covered with wax. In place of a pen they used a sharp instrument called a stylus. With the point of this they traced the letters in the soft wax. The leaves of the tablets were often tied together and opened like those of our books.

At first all the best books were in Greek. But soon beautiful poems and notable books began to be written in Latin, and the best rulers, like the Emperor Augustus, protected and rewarded scholars. Some of the finest Roman writers are not unworthy of comparison with even the great men of Greece. Foremost among these stands the famous poet, Vergil. His greatest poem tells how, when the city of Troy was destroyed by the Greeks, one of the bravest Trojan heroes, Æneas, escaped with his trusty followers and after lengthy wanderings and strange adventures landed in Italy. These heroes, sang Vergil, were the ancestors of the Roman race.

A very different kind of writer was the much-loved Horace. No stirring deeds of gods and heroes did he sing, but rather amused all by his genial and quiet humor.

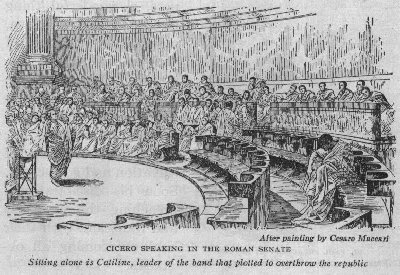

Another famous Roman was the great orator, Cicero, whose speeches are still studied by those who seek to improve themselves as orators and statesmen. By his eloquence Rome was once saved from bloodshed and possible destruction at the hands of Catiline and other desperate men, who, to escape from the consequences of their wicked deeds, plotted to overthrow the republic.

Yet, though the Romans thus had fine scholars and writers, most of them followed closely in the footsteps of the Greeks. In one respect, however, the Romans went far beyond any other ancient nation. .Roman judges and lawyers were by far the greatest the world

had yet known. Even in our own day their law books are studied and admired, and teach us much that is useful.

There were famous philosophers in Roman times, too, though none equaled Socrates and Plato. Perhaps the greatest were those called "Stoics." They taught that men should never give way to pain or pleasure, but do their duty no matter what happens. When a man endures terrible pain or misfortune with calmness, we still sometimes say, "He is a Stoic.”

51. The Coming of Christianity. The Stoics were good and noble men, but only a few very intelligent people could understand what they taught. If the Romans were to be saved from their cruelty and vice, something more was needed than the Stoic philosophy.

When it seemed that the world was to be ruined by its own wickedness, a wonderful thing happened. From Judaea, a far-distant province of the empire, came the strange tidings of the life and death of Jesus Christ, of Him who had perished on the cross but left behind a message of salvation and good cheer. Soon his disciples were preaching the news far and wide, and with their zeal overcoming all obstacles.

When it seemed that the world was to be ruined by its own wickedness, a wonderful thing happened. From Judaea, a far-distant province of the empire, came the strange tidings of the life and death of Jesus Christ, of Him who had perished on the cross but left behind a message of salvation and good cheer. Soon his disciples were preaching the news far and wide, and with their zeal overcoming all obstacles.

Nor was the message for the rich and great alone, for the new faith taught that all men are equal in the sight of God, and the poorest and humblest can share equally in the Christian's reward. At the head of the teachers of the new religion were Peter, a fisherman,  and Paul, a scholar, who knew how to speak so that all might understand. Though at first the high and noble would give little heed, many of the poor and lowly eagerly accepted the glad tidings.

and Paul, a scholar, who knew how to speak so that all might understand. Though at first the high and noble would give little heed, many of the poor and lowly eagerly accepted the glad tidings.

52. How the Early Christians Were Treated. At the beginning the Roman emperors cared little about the Christians. But when their numbers increased, trouble came. The Christians were suspected of forming a dangerous secret organization. When they met privately to celebrate the Lord’s Supper, it was thought that they plotted treason against Caesar. Under the laws of Rome people might believe what they liked about life and death, but all were required to worship the image of the emperor, head of the Roman state. This the Christians would not do. They thought it a sin to worship any one but God.

From time to time terrible persecution fell upon them. Those who would not obey the emperor were condemned to most awful sufferings. Often their death occurred in the amphitheater, and the spectators saw groups of Christians, men and women, kneel in prayer until wild beasts released from their cages sprang forth and devoured them.

The first terrible persecution was in the time of the brutal emperor Nero. This tyrant delighted the Roman mob by giving gladiatorial contests and games, but for his own entertainment and pleasure he committed awful crimes. According to a story which many people have believed, he cared so little for the welfare of the people that when the city of Rome caught fire he played and sang a poem that he had written about the destruction of Troy. When people cried out against his conduct, he cast the blame for the fire upon the Christians, and caused thousands to be put to death. He even lighted his gardens by having Christians bound to crosses and smeared with pitch, and then set on fire. Under Nero perished both St. Peter and St. Paul.

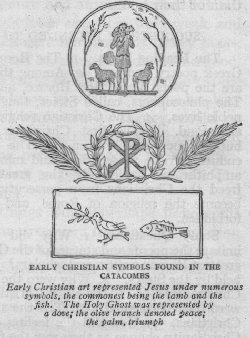

No wonder then that the early Christians met in secret places like the famous Catacombs, a name given to the narrow and dark underground passages constructed beneath a part of the city as burial places for the dead. Many of these galleries were dug out by  the Christians themselves, and here may still be seen the resting places of their dead, marked by the cross and by other symbols of the new faith.

the Christians themselves, and here may still be seen the resting places of their dead, marked by the cross and by other symbols of the new faith.

53. Christianity Triumphs. But sword and fire could not crush the religion of Christ. An ever increasing number of men and women adopted the faith which taught the martyrs to die so bravely.

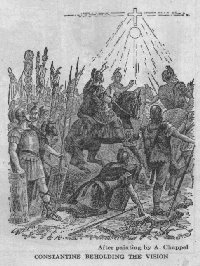

Finally there came a great civil war in Rome, waged by a number of powerful men each of whom claimed to be  emperor. Of these one was Constantine, who was proclaimed Caesar by the troops in the island of Britain. Since Constantine's mother was a Christian, he was well disposed toward this religion, and many Christians joined his forces.

emperor. Of these one was Constantine, who was proclaimed Caesar by the troops in the island of Britain. Since Constantine's mother was a Christian, he was well disposed toward this religion, and many Christians joined his forces.

There is a famous old story that as Constantine and his army were bravely marching against their enemies there was suddenly seen a cross blazing in the sky, and, underneath, the words, "In this sign thou shalt conquer." At any rate,  it is certain this able general thought it best to win the support of the Christians by putting the cross on his standard. (312 A.D.)

it is certain this able general thought it best to win the support of the Christians by putting the cross on his standard. (312 A.D.)

Under it he overthrew and destroyed all his foes and then triumphantly established his power as Caesar. As a result he declared that Christians should be tolerated, and he was finally baptized a Christian himself.

What a great change this was, when a supporter of the new faith occupied the imperial throne of the Caesars!

The worshipers of the old gods struggled hard, but the world was too wise to believe any longer in Jupiter and Juno. In time the pagan belief itself was forbidden, and the temples of the gods changed into Christian churches. Where once pagans had sacrificed to the deities of Olympus, now were heard Christian hymns and prayers, and Christian bishops and priests appeared everywhere in the empire beside Roman officials, judges, and soldiers.

The worshipers of the old gods struggled hard, but the world was too wise to believe any longer in Jupiter and Juno. In time the pagan belief itself was forbidden, and the temples of the gods changed into Christian churches. Where once pagans had sacrificed to the deities of Olympus, now were heard Christian hymns and prayers, and Christian bishops and priests appeared everywhere in the empire beside Roman officials, judges, and soldiers.

Just as the Romans had formerly shown themselves able to organize their vast empire, now they showed themselves equally skillful in establishing the new religion. In each village and country district a priest or minister was placed to preach to the people and conduct service in the church. Every large city had its bishop, who had control over all the priests in the surrounding region. In the capital of each province was the archbishop, a still more dignified officer, and finally, in the greatest cities like Rome, Constantinople, and Alexandria, were the most powerful bishops, or "patriarchs," of all.

Thus the Roman church was like another great Roman empire. But it was an empire of the souls of men rather than of their bodies.

The Leading Facts. 1. The Romans became very fond of Greek poetry and art. 2. Among the greatest of all Romans are the poets, Vergil and Horace, and the orator, Cicero. 3. The philosophers, called Stoics, taught that men should lead noble lives. 4. The Christian religion was taught by Peter and Paul. 5. The first Christians were mainly poor and humble men and women. 6. The early Christians bad to endure terrible persecution, and many lost their lives in the amphitheater. 7. Finally the great emperor, Constantine, freed the Christians from persecution. 8. Christianity then became the religion of Rome, and the pagan worship was forbidden.

Study Questions. 1. Why did the Romans do well to imitate the poems and statues of the Greeks? 2. Who were the greatest Roman writers and scholars? 3. State an important idea held by the Stoics. 4. Why were the poor so willing to accept Christianity? (5. If the early Christians were good men, why were they persecuted? 6. Tell the story about Nero and the Christians. 7. How did the feeling of the Romans regarding Christianity change as they saw the Christians die so bravely? 8. Who was Constantine? p. Why did he put the cross on his standard? zo. What was the chief result of his victory over his rivals? 11. Name the various kinds of officers in the Christian church of the Roman Empire.

Suggested Readings. Tappan, The Story of the Roman

People, 215-222; Yonge, Young Folks’ History of Rome, 285-

354; Harding, The City of the Seven Hills, 173-183; Guerber,

The Story of the Romans; Church, Stories from Virgil, 2-95,

210-266.

Next Chapter

Back to Table of Contents.

© 2001 by Lynn Waterman