Stories by Velma Ann Rogers Tower

Elmore City, Oklahoma

5 February 1979

To My Children, Grandchildren and Great Grandchildren

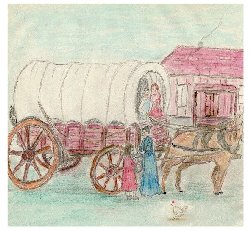

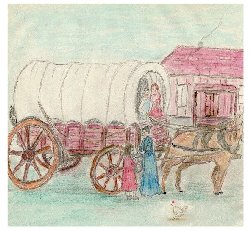

This section on Special Memories, I have written to give you a glimpse of the simplicity, beauty, and joy of growing up in the age that Ray and I

were born into. It was a wonderful age. The Covered Wagon was still a

common mode of travel, the Buckboard still bounced, and people still used

hacks, buggies and lumber wagons. People still traveled horseback through

need and common acceptance. The train was for those who had money or the

need for speed, yet we saw the Automobile become the common thing, also the

airplane.

Out store bought toys were few and far between, but we didn't miss

them. Most everyone had built in companionship. I think the most common

means of amusement was visiting. Children spent the night with other

children for no reason but the joy of being together. Adults and whole

families visited. They would hurry to finish the evening chores then walk

over or hitch up the team to the wagon and ride over to visit a neighbor.

While the grownups visited, the children played action games like "Drop the

Hankerchief, or Three Deep, or Hide and Seek." The Children whooped and

yelled and ran until it was too dark to see then went inside and played

quite games like "Hide The Thimble", or just sat and listened to the talk.

Out store bought toys were few and far between, but we didn't miss

them. Most everyone had built in companionship. I think the most common

means of amusement was visiting. Children spent the night with other

children for no reason but the joy of being together. Adults and whole

families visited. They would hurry to finish the evening chores then walk

over or hitch up the team to the wagon and ride over to visit a neighbor.

While the grownups visited, the children played action games like "Drop the

Hankerchief, or Three Deep, or Hide and Seek." The Children whooped and

yelled and ran until it was too dark to see then went inside and played

quite games like "Hide The Thimble", or just sat and listened to the talk.

I remember one special game that we played at Rocky Point

School-"Blackman". We marked off the bases then a zone that you had to pass

through to get from one base to the other. The biggest, fastest boys were

put in this zone to be the catchers. They would grab the big girls around

the waist and hold on for Dear Life until a helper came and patted them on

the back-one, two, three, you're out. Meanwhile the girls were yelling

screaming and kicking shins as they tried to get loose. While this was

going on, I walked from one base to the other. I stuck out my chest (In

those days I had more tummy than chest) and walked through, not just once,

but twice or maybe three times. I felt so elated. I thought the object of

the game was to go from one base to the other without being caught. After I

had married for several years that game popped into my mind and I sat down

and had a good laugh. It had finally dawned on me that I didn't have any

sex appeal in those days and that was why I was able to outwit everyone. I

had never seen or heard the word Sex and if I had seen it I would have

thought that someone didn't know how to spell six (6).

I never knew real fear as a child. I was seldom scared of anything,

except something like a centipede or a strange dog and even then my fear was

never panic. My Family had a simple Faith in God. Denominations didn't

play much of a part in my Religious Education until I was 13 or 14. Papa

and Mamma made me very aware of God but I had no fear of Him. I heard about

the Boogerman that would get me, but he was more like a myth than a reality,

so grew in a simple Faith and Joy of Innocence.

I never knew real fear as a child. I was seldom scared of anything,

except something like a centipede or a strange dog and even then my fear was

never panic. My Family had a simple Faith in God. Denominations didn't

play much of a part in my Religious Education until I was 13 or 14. Papa

and Mamma made me very aware of God but I had no fear of Him. I heard about

the Boogerman that would get me, but he was more like a myth than a reality,

so grew in a simple Faith and Joy of Innocence.

If some future child can get a glimpse of the Beauty of that age, I

have accomplished my purpose.

Love Mother

Velma Ann Rogers Tower

Special Memories by Velma Ann Rogers Tower

Our Family came to Oklahoma in September 1907. They left Taneyville,

Missouri the first day of September and stopped one day at Neosho, Missouri

and toured the Fish Hatchery and arrived at Prague, Oklahoma in Lincoln

County the 19th day of September. They camped where the present Town Park

is located. There was a Carnival in progress and Alfred Hammons and Doc

Adams boys slipped under the side of the tent to see the show. Alfred made

a Minister. I don't know what happened to those Adams boys.

Tradition has it that the family was on its way to Snyder, Oklahoma to

pick cotton, but Mr. Heatlely, the Prague Gin owner came out and talked them

into picking cotton for him in the area between Prague and Shawnee,

Oklahoma. This area was mostly in Pottawatomie County but in the Prague

Trade area and close to Econtuska and the Garden Grove School District.

There were, at least, five wagons in this wagon train. In our wagon

were Papa, Mamma, Bethany, Bethel, and Omah Ellen who was just a babe in

arms. Uncle Jake Adams had his wife, Tiny, and Norman and Opal and Etta

Hammons who rode with them because she loved Tiny and there was more room in

their wagon. Doc Adams had his sons, Harve, Charlie, Virgil, and Walter.

Uncle Ben Hammons had his children Bill, Alfred, Lillie and Etta who rode

with Uncle Jake. Aunt Mary had her daughters Linda and LouBelle whose father

was Martin Ingram who died of T.B. before she married Uncle Ben. Then they

had their children Rollo, Lonnie, and Chester (Now you see why Etta rode

with Uncle Jake). Chester and Belva were born to Uncle Ben and Aunt Mary in

Pottawatomie Co. after they settled there. They had another baby that was

still born a Lambdin, Oklahoma. Somewhere in this group was Uncle Orvis

Adams and other unattached young males. Names of others have been lost in

memory.

So, they came, with riding horses tied to the side and colts following

along, and cows tied to the tailgate and Uncle Jake's old hound dog

following behind, far enough to keep from being yelled at and near enough to

keep from being lost.

The cotton was ripe for harvest and the fields loaded down and they

were hungry for money. They picked and earned enough to see them through

the winter, then they rented farms on the Share Crop plan, which was good

for them. The landlord furnished the house and barn; such as they were, and

land and the farmer farmed it and gave the landlord a share of the crops

produced. The pasture belonged to the farmer and he could raise as much

livestock as the pasture would maintain. In good years, the farmer made a

good living. In bad years, he usually had a farm sale and sold everything

but the bare necessities to pay off his Bank Loan. Sharecroppers nearly

always borrowed each year to finance the buying of seed and farm machinery.

Omah Ellen died from measles. She is buried in Garden Grove Cemetery.

Mamma and Papa went back to Missouri in late 1909. Jobs were so few that

they almost starved. In 1910 when fall harvest neared, they loaded up the

covered wagon and came back to Oklahoma. They landed at Uncle Ben's place.

He had a big smokehouse made from sawed, green, cottonwood lumber and it had

a floor and stovepipe hole in it. Papa moved the family into that. There,

I was born 23 September 1910 with the address of Belmont, Oklahoma

Pottawatomie County. Dr. Brown from Belmont was the Doctor who delivered

me. Etta Hammons, Uncle Ben's daughter stayed with us during the day and

did the work for Mamma. It was an easy walk home at night since we lived in

their yard.

Grandma Adams, Mamma's mother, must have come to Oklahoma in 1908.

Uncle Jake and Tiny went back to Mo. After cotton picking was over. Tiny

was expecting a baby and wanted to be near her mother when it was born.

Around Christmas, her mother wanted to do some visiting and she brought her

houseplants to Tiny to care for while she was gone. Tiny had made herself

some new outing flannel petticoats and she had one on when she climbed up a

chair to put the plants on the fireplace mantle to keep them from freezing.

The fuzz on the petticoat caught fire from the open blaze and she burned to

death. She was home alone with her two small children, Opal and Norman.

Grandma moved in to take care of Opal and Norman. They came back to

Oklahoma that same year. I don't have a definite date, since it happened

before I was born.

Papa had rented a farm close to Econtuska. It had a small two-room

house nestled on a small prometory that dropped on one end of the house to

the pleasant valley below which in summer filled with cotton crops and a

smattering of growing corn. On the back and the other end it was protected

by bushy Blackjack Oaks and large Hickory Nuts and Pecan and Black Walnut

trees with a few Cottonwood trees shimmering and rustling in the sun. It

had a rude corncrib and drilled water well. The road ran behind the house

between two small hills to the valley below. A storm cellar had been dug in

the side of the prometory that faced the valley. It had stovepipe and

upright door that you could stand in and face the valley below. It was more

like a sod house than a cellar. It had probably been dug for that before

Statehood and the land was opened for settlement.

Uncle Orvis (Grandma Adam's youngest child) and Aunt Mary moved into

the Hill Cellar after they were married while waiting to get possession of a

farm. One of my favorite games was to take a long running jump to the top

of the Cellar then jump as high as possible, two or three times. Uncle

Orvis caught me and very sternly told me to stop that. Every time I jumped

the dirt sifted down on Aunt Mary's white, sheet bedspread and on the table.

He spent lots of time instructing me on methods of becoming acceptable,

well-behaved child. This was about 1912.

While we lived on this quiet farm in it's secluded peaceful

surroundings among the tall tree, I didn't have any real fear but I did

listen to the old wives takes and superstitions--One day while walking down

the road behind the house, I saw a large Centipede crawling up the bank. Now

I had heard that if a Centipede touched you that your flesh would rot and

fall off. I yelled as loud as possible and Papa came with his hoe and killed

it. A hoe, not a gun, was a farmer's weapon. He could use it to kill a

snake or wild animal or to kill a man. It was always razor sharp because it

was in constant use to chop weeds, grass and young sprouts also to till the

soil in the vegetable garden.

One day I chanced on one in the yard that had its sharp blade turned

down and embedded in the soil, so I placed my feet on the hoe's back, a foot

on each side of the handle just behind the blade and tried a balancing act.

The hoe turned up and the blade caught my left foot just under the two outer

toes and cut to the bone. We did not go to the Doctor to get them sewed up.

My mother cleaned my foot with Kerosene, made a footlet from an old worn

sheet, put it on my foot and then she and papa prayed for me. Those toes

healed perfectly and I still have them and I'm near eighty. What a

wonderful thing Prayer was for the early settlers of Oklahoma.

Bethany had Typhoid while we lived there. She was very ill. Her hair

started falling out and everyone assured her that it would probably come

back in Curly. She had such pretty Auburn hair that she didn't need curls.

I was told over and over, "Don't taste any of her left over food." They

catered to any imaginary craving that she might have in their effort to

restore her health, so I was tempted but scared too much to taste.

While she was recovering, someone brought her a baby squirrel. It

scampered all over the house and up and over people and ate from our hands.

It took its corn up over the door mantle and stored it there. One day

someone left the door open and it was gone in an instant. We missed it but

it was glad to have its freedom.

While she was recovering, someone brought her a baby squirrel. It

scampered all over the house and up and over people and ate from our hands.

It took its corn up over the door mantle and stored it there. One day

someone left the door open and it was gone in an instant. We missed it but

it was glad to have its freedom.

SPENDING THE DAY AT GRANDMA'S

In the early fall of 1914, before Dorothy was born, Papa had a load of

cotton ready to gin and sell. Mamma wanted to go to town with him so they

talked me into spending the day with Grandma. All dressed up in my red Pony

Fur Coat, I climbed up to the top of the load of cotton where Mamma was

already curled up and Papa sat with his feet hanging over the front of the

wagon with the reins in his hands. When we got to Grandma's turn off which

was about a quarter of a mile off of the road, we could see everyone picking

cotton in front of the house.

The cotton rows ran toward the road but they were picking with their backs

toward us. They had their shoulder strap looped over one shoulder and their

long ducking sacks dragging along behind full of lumps that looked like a

chicken snake that had just swallowed a nest of eggs. The field was on a

bottom piece of land and the cotton grew tall in places. Papa and Mamma

were afraid that I might get scared or lost in the tall cotton so they stood

up and called and called but no one heard them. They finally set me off and

watched me down the row until I reached Opal.

It was like going through a tall green forests, except that the plants

were no more than four feet tall, though they were over my head most of the

time. I sneaked up and sat on Opal's sack. When she started to pull down

the row and felt that extra weight she knew something was wrong. We laughed

and laughed, she would laugh then, I would laugh. The cotton smelled warm

and dusty, but it smelled homey too. I had ridden the sacks ever since I

was born as one adult or another picked cotton. Time and money were too

scarce for anyone to stay out of the field unless they were really sick.

Before the day was over Uncle Jake gave me a tow sack with a strap that went

over my shoulder and I picked cotton and earned my first money.

It was like going through a tall green forests, except that the plants

were no more than four feet tall, though they were over my head most of the

time. I sneaked up and sat on Opal's sack. When she started to pull down

the row and felt that extra weight she knew something was wrong. We laughed

and laughed, she would laugh then, I would laugh. The cotton smelled warm

and dusty, but it smelled homey too. I had ridden the sacks ever since I

was born as one adult or another picked cotton. Time and money were too

scarce for anyone to stay out of the field unless they were really sick.

Before the day was over Uncle Jake gave me a tow sack with a strap that went

over my shoulder and I picked cotton and earned my first money.

We went to the house at noon to eat. Grandma not only didn't have a

highchair; she didn't have enough chairs to go around. She put me at the

corner of the table in front of a pretty little plate that had a flower in

the center and told me to stand and eat (this was a common custom, but I

didn't like it. I thought Uncle Jake should have taken me on his knee like

Papa did at home when someone smaller needed my highchair. I didn't like

her saltpork or her mustard greens either.)

We went to the house at noon to eat. Grandma not only didn't have a

highchair; she didn't have enough chairs to go around. She put me at the

corner of the table in front of a pretty little plate that had a flower in

the center and told me to stand and eat (this was a common custom, but I

didn't like it. I thought Uncle Jake should have taken me on his knee like

Papa did at home when someone smaller needed my highchair. I didn't like

her saltpork or her mustard greens either.)

LITTLE STRANGER

Dorothy was born in the little two-room house on the secluded farm. I

don't remember much about Dorothy's birth. After spending the night with

Grandma and Opal she was there in bed with Mamma and wearing my gowns. I

loved Opal because she always petted me. She always loved the smallest

child and I was the smallest, Odessa, who was born 1913, but Odessa's

Mother, Aunt Mary Adams was sickly, nicey nice, cleanly clean, and

sanctimoniously Holy and good, so she had as little to do with the lusty,

earthy family of Uncle Orvis as possible. In times of illness she was there

like a Saint and my parents often spoke of her as a Saint, but she didn't

whole heartedly approve of the Adams Clan and with good reason. Two of

Mamma's brother s liked to partake of Alcoholic beverages to excess and when

provoked could curse in the most colorful words ever hear by man. They had

hearts of gold and reached out and cared for Mamma's family whenever there

was a need. There were times when they appeared to beyond redemption.

Like I said, I loved to go see Opal because she petted me. After being

together thirty minutes she might pinch me till I was back and blue or pull

my hair or bite me or scratch me but somehow I knew that she loved me and I

loved her. After spending the night with her and grandma, I came home and

there in bed with Mamma was that itty, bitty stranger and she was wearing my

gown, the one that Mamma had crocheted around the collar with pink and blue

thread. I didn't think much of her but I didn't throw the fit that Opal

used to tell about. I didn't really dislike her; I just didn't like for her

to be wearing my gown. No one told me those gowns were mine. They were too

small for Bethany or Bethel so they had to be mine. I was born with an

innate love of color and the pink and blue lace satisfied that love.

I was allowed to name Dorothy, I'm sure with lots of guidance but my

ego was soothed. After that I have spotty memories of her. Suddenly I was

seated on the bench at the table between Bethel and Bethany but I loved

that. I felt so grown up. They assured me that my highchair was too weak

to hold me up and a big girl shouldn't be in a highchair. It has raised

three babies besides me and made a trip back to Missouri. That was a sturdy

chair. Mamma took it on the Harvest trip and after she died Grandma had it

for several years.

I was aware of Dorothy when she soiled her diaper and ran for Mamma as

fast as my legs would carry me and then I ran for the yard. I remember when

she swallowed Mamma's thimble because everyone laughed so much about finding

it. I remember borrowing the neighbors Sulky to pull her to town because I

resented being the one who had to ask to borrow it. I remember that she was

an Adam's child, fair, blue eyed, hot tempered, and looked like Mamma. For

these reasons and because she was the baby, the Adam's clan were partial to

her. She always fought Mamma right down the line on everything that Mamma

undertook to make her do. I was always outraged at this. If Mamma or Papa

told me to do something, I felt that I had to do it without any and, if, or

buts. Maybe Mamma had taught me that a Peach Tree switch was a great

persuader. I have no memory of being taught not to sass but I do remember

being spanked by Mamma. She firmly believed in it. She had the efficient

hand in the world. She could raise a blister on backsides before one knew

what she had in mind.

Papa on the other hand invited you to the bedroom and kneeled with you

while you asked God to forgive you. He would ask God to forgive you. I

would have preferred the swift spank. It didn't touch the mind. A quick

spurt of pain and one was cleansed of all guilt and was ready to sin again

at the first whim. In spite of my firm belief in the authority of my

parents, I spent a lot of time on my knees at Papa's insistence, asking God

to forgive me.

I don't remember living in any other house until after Dorothy was

born. Uncle Jake and Harrison Roller had moved to the Rocky Point School

District in Lincoln Co. Oklahoma, so Papa moved too. He rented a farm that

had a good rock house made from red sandstone. It had a good barn and a

good dug well just off of the back porch. The soil was poor, thin and

scraggly. I remember Papa coming from the field at first dusk. I could

hear the jingle of the harness before I could see him, then I would smell

the hot sweaty horses and then I'd go down the lane to meet him and he'd

take my hand as we walked to the barn lot where he unharnessed the team.

The horses rolled over and over in the dust then headed for the barn to be

fed. After that, we headed for the kitchen light where Papa stopped on the

back porch and washed in the tin washbasin. Then we went in to a supper of

hot corn bread and milk and whatever was left from the noon meal, but

always-hot cornbread and milk. One other dish comes to mind. Mamma had made

cottage cheese and rounded it up in the bowl and liberally sprinkled it with

pepper. She always put sugar in her cottage cheese and I still love cottage

cheese with sugar.

It was while living in the Rock House that Bethany caught the Red Bird.

She tied a string on its leg and tied it to the well post. It was a beauty

but so scared that it flew frantically and beat itself on the well post

until she felt sorry for it and turned it loose.

It was while living in the Rock House that Bethany caught the Red Bird.

She tied a string on its leg and tied it to the well post. It was a beauty

but so scared that it flew frantically and beat itself on the well post

until she felt sorry for it and turned it loose.

In 1916, after the crops were planted, things started shaping up for

another bad year. Papa had a farm sale and sold off everything but the bare

necessities. These, we loaded into a covered wagon and set out for the

wheat harvest. Uncle Orville was working for the railroad in Northern

Oklahoma, so we stopped with them until Papa could sign on with a harvest

crew. We traveled into Kansas following the Harvest. Part of the time

Mamma managed the Soup Wagon. The wagon was fitted with a stove, table, and

benches and the hands came at noon to eat soup, cornbread and pie. In good

weather we slept on quilts under the sky, otherwise we spread the feather

bed on the floor of the wagon and slept there.

One night while sleeping out, I awakened and saw Bethany's auburn hair

spread over the pillow and thought it was a strange dog. I cried out and

woke everyone up. They teased me for weeks about that.

When Harvest was over, we headed for Boynton, Okla. Uncle Ben was

farming there and there was quite a bit of Oil interest at that time. Uncle

Orvis beat us there and Uncle Ben's daughter Lily. Papa landed a job and

started hauling for the Oilfield, bought lumber and built a small house.

One day, I asked Mamma to let me go play with Belva Hammons who was my

favorite cousin. We decided to take a walk down through the pasture. We

walked by Aunt Mary and Uncle Orvis's house and Aunt Mary led O'dessa go

with us. On our walk, we spied a huge red anthill. Now we hated red ants

because we had been stung by them more than once. We decided to stomp them

to death. We began stomping and the faster we stomped the faster the ants

came out of that hill. Finally when we were loosing and our legs stinging

like fire, we retreated and went to Aunt Mary Adams's house. When she saw

us coming and heard O'dessa crying, she came out of that house as mad as a

wet hen, took O'dessa up and washed her in soda water and cooed and petted

her while she glared at us. She then gave us a basin of water and told us

to wash. I was mad at her for years because she didn't give us some

sympathy too. That is the only time that I remember her being mad at me. I

even wished that I had scratched her big boo eyes out. Mamma left me with

her one hot day while she worked in the field. Aunt Mary put me on the bed

and lay down by me to take a nap. This was before O'dessa was born and she

needed a nap, but I didn't. When she had fallen asleep, I took my fingers

and pulled her eyes open and said "Aunt Mary, open you're big boo eyes." She

had the most beautiful blue eyes I ever saw. I can remember pulling her

eyes open. I can also remember how red and angry O'dessa's little fat legs

looked after the ants stung her..

One day, I asked Mamma to let me go play with Belva Hammons who was my

favorite cousin. We decided to take a walk down through the pasture. We

walked by Aunt Mary and Uncle Orvis's house and Aunt Mary led O'dessa go

with us. On our walk, we spied a huge red anthill. Now we hated red ants

because we had been stung by them more than once. We decided to stomp them

to death. We began stomping and the faster we stomped the faster the ants

came out of that hill. Finally when we were loosing and our legs stinging

like fire, we retreated and went to Aunt Mary Adams's house. When she saw

us coming and heard O'dessa crying, she came out of that house as mad as a

wet hen, took O'dessa up and washed her in soda water and cooed and petted

her while she glared at us. She then gave us a basin of water and told us

to wash. I was mad at her for years because she didn't give us some

sympathy too. That is the only time that I remember her being mad at me. I

even wished that I had scratched her big boo eyes out. Mamma left me with

her one hot day while she worked in the field. Aunt Mary put me on the bed

and lay down by me to take a nap. This was before O'dessa was born and she

needed a nap, but I didn't. When she had fallen asleep, I took my fingers

and pulled her eyes open and said "Aunt Mary, open you're big boo eyes." She

had the most beautiful blue eyes I ever saw. I can remember pulling her

eyes open. I can also remember how red and angry O'dessa's little fat legs

looked after the ants stung her..

Another time Uncle Orvis bought a wagonload of fruit and selling it

from the back of the wagon. He put one of the sideboards across a couple of

barrels and put the prettiest fruit on them. I happened along (I was barely

six) and he had an errand to do, so he said, " Velma watch this for me for a

few minutes." There was a beautiful, luscious pear on that board, only one

pear. I looked at it and waited for him to come back and I got hungrier and

hungrier. I ATE THAT PEAR! When her got back, he had a fit. He never did

succeed in making me an acceptable child. I started to school at Boynton,

Oklahoma. Bethany went to school too. Bethel must have gone but I have no

remembrance of him going. Bethany walked with me to school. The school was

short distance from our house. We could see it from the front door but it

seemed miles away to me. After Papa got sick, Bethany stayed home to help

out. I recited the lessons perfectly and when I read, I read every word. I

had listened to the others read and had memorized the stories. I didn't

know one word from another.

The 12th of October 1916, Papa died from Pneumonia (They called it

Congested Chills). In his hauling job he had to be out in all kinds of

weather and one of those cold rainy fall days caught him out without rain

wear. He caught cold and it developed into Pneumonia. The family and

friends came to sit with him. They anointed him with oil and prayed for

him, but around 8:30 or 9:00 P.M. October 16, 1916, he just quit breathing.

Mamma had put Dorothy and me to bed on the opposite side of the room

and removed the oil lamp to the kitchen. Just as I was almost asleep, I

seemed to see a scroll float from Papa and float over our bed and hover

there for a second then float Heavenward. I listened for Papa's breathing

and knew that he was gone. Uncle Orvis came in just then and told the

others that he was gone. I puzzled over the vision of the scroll for years

and finally concluded that it was Papa's blessing for us.

Mamma had put Dorothy and me to bed on the opposite side of the room

and removed the oil lamp to the kitchen. Just as I was almost asleep, I

seemed to see a scroll float from Papa and float over our bed and hover

there for a second then float Heavenward. I listened for Papa's breathing

and knew that he was gone. Uncle Orvis came in just then and told the

others that he was gone. I puzzled over the vision of the scroll for years

and finally concluded that it was Papa's blessing for us.

I was hurt about loosing Papa but not desolate. He was a devout man

and I firmly believed that he had gone to Heaven. Mamma was still there

like the Rock of Gibraltar and I felt secure. I think that I loved Papa

most but Mamma was the anchor that we tied to.

Uncle Jake was called at Prague, Oklahoma. When Mamma had problems, he

always came to her rescue. He came and took over and made all of the

arrangements and settled plans for our future. Harrison Roller and Uncle

Ben Hammons and Uncle Orvis Adams all gave moral support and probably

financial support as well. I was too young to know the details.

They buried Papa in the Boynton, Oklahoma Cemetery just to the left of

the gate as you go in. On that Sunny October day the wind was blowing the

grass till its top bowed and touched the earth as if in Prayer. The men of

the family dug the grave with a pick and shovel. The sides of the grave

were rough and the grave was larger than the pine box that held his coffin

and this outraged me, a six year old. I felt that the sides should be

straight and even and smooth like the sides of a dug dirt cellar. It didn't

occur to me that the weather was hot and dry and the soil would come up in

chunks. Those rough walls of the grave seemed inexcusable to me, especially

so since my beloved Papa was to be put in that grave. The men of the family

put his coffin in the pine box at the house and then lifted it into the

wagon that had played such a part in his life. Mamma, Dorothy and I rode in

the wagon with him to the Cemetery. The others walked which was about two

miles, but people walked more in those days. Uncle Orvis carved his name on

big sandstone and put that at the head of his grave. That rock stood until

1973, at least. It weathered until it looked like a tree stump but part of

the letters were still discernable. Dorothy, Bethel, and I bought a new

stone for him and one for Mamma too.

They buried Papa in the Boynton, Oklahoma Cemetery just to the left of

the gate as you go in. On that Sunny October day the wind was blowing the

grass till its top bowed and touched the earth as if in Prayer. The men of

the family dug the grave with a pick and shovel. The sides of the grave

were rough and the grave was larger than the pine box that held his coffin

and this outraged me, a six year old. I felt that the sides should be

straight and even and smooth like the sides of a dug dirt cellar. It didn't

occur to me that the weather was hot and dry and the soil would come up in

chunks. Those rough walls of the grave seemed inexcusable to me, especially

so since my beloved Papa was to be put in that grave. The men of the family

put his coffin in the pine box at the house and then lifted it into the

wagon that had played such a part in his life. Mamma, Dorothy and I rode in

the wagon with him to the Cemetery. The others walked which was about two

miles, but people walked more in those days. Uncle Orvis carved his name on

big sandstone and put that at the head of his grave. That rock stood until

1973, at least. It weathered until it looked like a tree stump but part of

the letters were still discernable. Dorothy, Bethel, and I bought a new

stone for him and one for Mamma too.

Mamma went back to Prague with Uncle Jake. She took Dorothy with her.

Bethel, Bethany and I stayed to load the household goods on the wagon and

drive back to Prague. We spent the last day in Boynton with some extremely

kind people. I don't remember their name but I do know that they were not

family. That man helped put the tarp on the wagon and that lady baked a

fifty-pound lard can full of Molasses cookies for us to eat on the way to

Prague. She was so afraid that we would run out of food before we got to

Prague.

Mamma went back to Prague with Uncle Jake. She took Dorothy with her.

Bethel, Bethany and I stayed to load the household goods on the wagon and

drive back to Prague. We spent the last day in Boynton with some extremely

kind people. I don't remember their name but I do know that they were not

family. That man helped put the tarp on the wagon and that lady baked a

fifty-pound lard can full of Molasses cookies for us to eat on the way to

Prague. She was so afraid that we would run out of food before we got to

Prague.

I love the memory of those devout, kind people. They were poor also,

but gave of their sustenance to keep from worrying about us. It took

Christian love to take us in and send us on our way with enough food to see

us through. The night that we spent with them I had a terrible cold and was

real croopy. Before I went to bed, she mixed kerosene and lard and put it

on a wool cloth and pinned it on my chest. It smelled terrible and felt

worse. As soon as she blew out the Kerosene lamp Bethany whispered to me

that I could take it off but not to say anything lest I hurt her feelings.

It never occurred to me to be afraid to make that trip. I was used to

Bethany taking care of me. I don't remember many details of the trip,

except that I got real tired of molasses cookies. We must have cooked but I

don't remember it. We had harness trouble by Boley, Oklahoma, a Black

Community, and Bethel was out by the horse's head crying. A colored man

came along, took a piece of bailing wire and wired the harness together.

This impressed us because we had built in prejudice, and had had very little

contact with black people.

The homecoming was wonderful. The Adams Clan had their faults, high

tempers, nasty mouths at times, and a healthy disregard for staid

conventions, but they possessed double portion of warm love. We were

greeted with that warm love and great rejoicing, and, if Opal and I were

fighting and pulling each other's hair a day or so later, no one worried too

much.

Uncle Jake rented a farm for Mamma close to him. Bethel, Bethany, and

Mamma planned to farm it with Uncle Jake's help. We moved into the two-room

house to await the spring planting time. I remember chills every day that

winter. We all had malaria. We would shake and shiver and freeze. Soon

the chill would pass and we would go about our business.

Christmas was special for me that year. We knew that we were as poor

as Church Mice but we didn't expect much. After we had gone to bed, I heard

Bethany and Mamma talking. They planned to make a toy horse for me out of

an old Pony Fur (fake fur) coat. I felt guilty about pretending to be

asleep, but I couldn't make myself tell them that my horse wouldn't be a

surprise when I found it in my stocking on Christmas morning. I think that

Bethel got Papa's razor. I don't remember what Dorothy got. Bethany

probably received nothing but the joy of being a co-conspirator. Bethany

went into the field and scrapped cotton to stuff that horse (after the

cotton was picked clean, a few tufts were always left in the boll and with

patience and hard work a few pounds could be scrapped. Sometimes the scrap

cotton was carded and used as filler for quilts.) Mamma put sticks in its

legs to make it stand up, and buttons for its eyes and yarn for its tail and

mane. I didn't enjoy playing with it but I loved and cherished it.

Christmas was special for me that year. We knew that we were as poor

as Church Mice but we didn't expect much. After we had gone to bed, I heard

Bethany and Mamma talking. They planned to make a toy horse for me out of

an old Pony Fur (fake fur) coat. I felt guilty about pretending to be

asleep, but I couldn't make myself tell them that my horse wouldn't be a

surprise when I found it in my stocking on Christmas morning. I think that

Bethel got Papa's razor. I don't remember what Dorothy got. Bethany

probably received nothing but the joy of being a co-conspirator. Bethany

went into the field and scrapped cotton to stuff that horse (after the

cotton was picked clean, a few tufts were always left in the boll and with

patience and hard work a few pounds could be scrapped. Sometimes the scrap

cotton was carded and used as filler for quilts.) Mamma put sticks in its

legs to make it stand up, and buttons for its eyes and yarn for its tail and

mane. I didn't enjoy playing with it but I loved and cherished it.

That Christmas day, we made molasses candy (taffy). We spent hours

pulling it. We made twists and braided it, and made all kind of shapes.

Before the day was over, we were tired of the taste, smell, and color of

taffy. I did have enough foresight to hide a piece for future eating. I

hid it on the little shelf on the wall clock and I got into trouble over

this. Damp weather came and that taffy melted and ran on the clock and made

it sticky. It had to be washed with a damp cloth to remove the sticky

feeling. I was sternly lectured.

In January Mamma took Pneumonia. Neither Papa or Mamma believed in

taking medicine, but Uncle Jake who had not been converted to the Holiness

Faith, was more practical. He called old Dr. Curfoot who said her recovery

was doubtful. He told Uncle Jake that he might save Mamma but the medicine

would probably cause a still birth for her unborn baby. Uncle Jake opted

for saving Mamma. Her baby boy, Leland, was still born the 23ed or 24th of

January. He was a beautiful well-formed baby. They laid him on Mamma's

sewing machine and he looked like a doll lying there.

Mamma died the 26th of January. She was buried in Garden Grove

Cemetery where so many of the family were buried, in Pottawatomie County

Oklahoma. The day was a bitterly cold day and we drove from Prague to

Garden Grove in the wagon. We heated a rock and put it below our feet and

wrapped up in quilts and we were still cold. During Mamma's Funeral I felt

the most excurating pain that I have ever felt I felt so alone. Into this

breach, came Grandma and Uncle Jake. We moved in with them and Opal and

Norman. When we got back to their home, Grandma fed everyone then took a

cane back chair to the living room and sat down and cried. She wailed the

most heart-rending sound I ever heard. She said not a word, just cried and

wailed her Heart out. Then she left her chair and went about her household

chores.

Four extra people were added to the four of Uncle Jake's

responsibility, which was too much for any one man. I never felt unloved or

unwanted with him. He was never begrudging.

The year after Mamma died was one of my most rewarding. Because

Grandma was almost blind, her supervision was somewhat lax. I took full

advantage of this to go my own way. I explored everything within walking

distance. Starting with spring, we, Opal, Norman, Bethel and I picked wild

onions, which we cooked with scrambled eggs. We picked Sheepshire (We said

"Sheepsgower".) and made Sheepshire pie which tasted like Rhubarb. We

waded, or I, waded the gullies after every rain, and stood under the eaves

and took showers during the rain, sometimes fully clad, built playhouses

under the apple tree when it was in bloom (I still love the smell of apple

blossoms) and we robbed the birds nest of their beautiful eggs, and after

those that escaped our robbing, hatched, we took the babies and tried to

make pets of them. Wrong? It was. We were too young and undersupervised to

know that we were interfering with nature. I put my baby mocking birds on

the oven of an old iron cookstove that sat behind the smokehouse and the

cats ate them. We ate green apples and plums with salt and suffered

terrible tummy aches. We ate fresh roasting ears (We said roshen yers)

until our appetite was sated, and nothing ever tasted so good before or

after. We swam in the horse trough and muddy pond. I hated the pond

because it felt rough on my feet. We made loblollies in the yard after the

spring rains. We found a soft spot and worked our feet up and down till the

mud looked like chocolate icing and competed to see who could make the

smoothest loblolly. In between times Uncle Jake herded us to the field and

tried to get the corn weeded and the cotton chopped. As he plowed out of

sight, we leaned on our hoes and played games. We needed a strong hand and

he was too busy plowing and planting and grandma couldn't see well enough to

know that we were goofing off. Bethany carried her part of the load before

she got a job and tried to earn enough money to help out.

When the Fall Season came, we were supposed to help harvest the crops,

but again we played and goofed off. We skated on the pond, and on cold days

built bonfires to keep warm and roasted pecans in the hot ashes while we

warmed. We hunted rabbits, possums and anything that had fur because Bethel

and Norman sold the pelts. We ate redhaws, blackhaws, persimmons, and wild

grapes on our hunting forays and came home to eat Grandma's thick dried

apple pies. We had been made to peel and slice them and place them on a

sheet and put it on the porch roof while the apple dried.

Grandma was one of the poorest cooks in the world. My sister, Dorothy

says she made green biscuits. She has a big round flat pan and she filled

it with flour, then made a hollow place in the center and into that put her

sour milk, lard and soda. She then worked this into a dough, which she

rounded by the handful into a biscuit, then placed on the greased bread pan

and turned each one over once and put in the hot oven to bake. She couldn't see well enough to see that the soda wasn't dissolved well and sometimes a pinch of the soda would leave a greenish

spot, which I always pinched out and fed to the dog or chickens. The rest

of the biscuit was good. I didn't mind the green spot one bit. She was a

master at making cornmeal mush. She set her iron pot full of water on the

hottest part of the cookstove and when it started to boil, she'd take a

handful of cornmeal and stir the water with a big spoon as she slowly

dropped the cornmeal into the boiling water with the other hand. I've

always said that Grandma could work 18 hours a day on a bowl of cornmeal

mush and a cup of Sassafras Tea and go out and dig the Sassafras. She loved

her Sassafras Tea and Cranberries, and her cup of boiling water for

breakfast. She didn't touch coffee or regular tea but firmly believed a cup

of hot water every morning was good for you.

That year was a golden year for me and the other kids but a nightmare

for poor overworked, big-hearted, indebted Uncle Jake. He didn't need an

excuse to nip at his home-distilled whisky, but had he needed one, he had

ample.

The next year, 1918, Bethel and Bethany decided to make a crop with

Uncle Orvis. Aunt Mary was in poor health. Her baby, Vanite was born in

January and died in May. Aunt Mary was unable to do more than the minimum

of work. We lived under the same roof but she had her quarters and we had

ours. Bethany was the boss and she had a much firmer hand than did Grandma.

She had learned from Mamma that peach tree tea (switch) was a wonderful

reformer, and if it wasn't available then ironweeds were a good substitute.

We toed the mark, but it, too, was a good year for me. While Bethany,

Bethel and Uncle Orvis toiled in the field, I cooked our food and cared for

Dorothy. I oversupervised Dorothy and undercooked the food. The food was

simple--beans and corn bread or boiled potatoes and corn bread. I cooked

this and took it to the field at noon. Dorothy had boils on her thigh and

had trouble walking, so I'd carry her a little way, put her down go back and

get the bucket of food and repeat this until we reached the field. While we

waited for them to reach the end of the row, we would build miniature

cellars. We'd find a nice fresh bit of turned soil and bury our feet in it

then try removing our feet without disturbing the roof part of the soil.

This took practice and skill. We also cut weed and built miniature brush

arbors. Real brush arbors were numerous in the summer before

air-conditioning.

I must have been born with double streak of Scotch blood, anyway,

nothing went to waste. One day I took the cornbread out of the oven and

dropped it in the middle of the dirty floor. As it dropped, it turned

upside down. I scraped it up and took it to the field. Bethel nearly

raised the heavenly roof. He had never eaten bread with sand in it.

Bethany looked so sad as she took her bread in her left hand and brushed it

with the outstretched finger on her right hand, then she would blow on it to

try to remove the sand. I'll never forget how tired and sad she looked as

she tried to eat that mess, at seven and a half years, I learned to feed

such messes to the chickens and start over.

I must have been born with double streak of Scotch blood, anyway,

nothing went to waste. One day I took the cornbread out of the oven and

dropped it in the middle of the dirty floor. As it dropped, it turned

upside down. I scraped it up and took it to the field. Bethel nearly

raised the heavenly roof. He had never eaten bread with sand in it.

Bethany looked so sad as she took her bread in her left hand and brushed it

with the outstretched finger on her right hand, then she would blow on it to

try to remove the sand. I'll never forget how tired and sad she looked as

she tried to eat that mess, at seven and a half years, I learned to feed

such messes to the chickens and start over.

That was the year that the sun eclipsed. The chickens all went to

roost. They looked so silly as the sun came out, as if to say, "Short

night." We had smoked pieces of glass over the lamp chimney and we all

looked at the eclipse through them.

That was also the year that bethel cut my hair. I always wore short

hair but had a topknot that was pulled back from my forehead and braided.

On Sunday I wore a ribbon on it or for dress up too. I wanted bangs. One

day when all of the grown ups were gone, Bethel agreed to cut bangs for me.

He cut them too short and thin and they stood straight up. He wet them down

and combed them but they still stood up. He dug out Papa's straight edge

razor and shaved them off. I had two wishes granted that day, Bangs and a

high forehead. When Bethany came home, she combed down my hair over my

forehead and cut thick bangs.

That was also the year that bethel cut my hair. I always wore short

hair but had a topknot that was pulled back from my forehead and braided.

On Sunday I wore a ribbon on it or for dress up too. I wanted bangs. One

day when all of the grown ups were gone, Bethel agreed to cut bangs for me.

He cut them too short and thin and they stood straight up. He wet them down

and combed them but they still stood up. He dug out Papa's straight edge

razor and shaved them off. I had two wishes granted that day, Bangs and a

high forehead. When Bethany came home, she combed down my hair over my

forehead and cut thick bangs.

When this year was over, Uncle Orvis went back to work for the

railroad. Bethany went to town and got a job. Bethel joined the Army as

soon as he could convince them that he was old enough. Dorothy and I went

back to live with Grandma and Uncle Jake.

After Mamma died, I became the keeper of Dorothy. All of the family

impressed on me the fact that Grandma was too blind to watch her and it was

my responsibility to take care of her. The Lord knows that I tried. I

washed her; I dressed her; I washed her clothes on the washboard; I ironed

her clothes with Grandma's old iron handled Sad Iron that had been heated on

the wood stove; Grandma threw a quilt on the cook table and put a flat pan

on it with salt in it. She would say, "Velmar, rub the iron the salt and

start ironing where it won't show. That way if there is smut on the iron,

it won't be on top where it can be seen."

I saw that she got her share of any treat that came our way. I gave

her medicine. Once when she was sick I took a pill with a glass of water

and saw that she put it in her mouth and took a sip of water then made her

open her mouth while I peered in. I was suspicious all of the time.

Finally, I went outside and pawed through the grass under the window, and

found every pill. She had punched them through a hole in the window. (Mom

always said she sucked the candy coating off first)

I saw that she got her share of any treat that came our way. I gave

her medicine. Once when she was sick I took a pill with a glass of water

and saw that she put it in her mouth and took a sip of water then made her

open her mouth while I peered in. I was suspicious all of the time.

Finally, I went outside and pawed through the grass under the window, and

found every pill. She had punched them through a hole in the window. (Mom

always said she sucked the candy coating off first)

I had never heard the word Psychology, but I could have used some of

it. As we grew, we developed a Generation Gap before the world knew about

generation gaps. I prodded, cajoled, and pinched and slapped and she

resisted. Like the time I tried to teach her to say Red. She was seven and

past the age for baby talk. I shaped my mouth and had her to look at it and

red. She shaped her mouth looked at me then way up high said "Yed"! This

went on for, at least, thirty minutes with each of us getting higher and

louder. It finally dawned on me that she was saying ""Yed" just to aggravate

me. I drew in my horns and let her say Yed until she was ready to say red.

We stayed with Uncle Jake until I was 13. Uncle Will came and got us

and took us to Missouri. He made us go to school and Church regularly and

we had plenty to eat and wear, but I wouldn't trade those Harum, Scarum days

with Grandma and Uncle Jake for the world. With them the food was sometimes

Mush and Milk or just gravy and bread, but I felt content. I had freedom to

do the childhood things and to dream and I did both. My Chinaberry beads

made by my own hand and strung on a raveling string, or my oakball beads

were as satisfying to me as the finest string of pearls.

Continue

© 2002; by Mary Patricia Ruble

Out store bought toys were few and far between, but we didn't miss

them. Most everyone had built in companionship. I think the most common

means of amusement was visiting. Children spent the night with other

children for no reason but the joy of being together. Adults and whole

families visited. They would hurry to finish the evening chores then walk

over or hitch up the team to the wagon and ride over to visit a neighbor.

While the grownups visited, the children played action games like "Drop the

Hankerchief, or Three Deep, or Hide and Seek." The Children whooped and

yelled and ran until it was too dark to see then went inside and played

quite games like "Hide The Thimble", or just sat and listened to the talk.

Out store bought toys were few and far between, but we didn't miss

them. Most everyone had built in companionship. I think the most common

means of amusement was visiting. Children spent the night with other

children for no reason but the joy of being together. Adults and whole

families visited. They would hurry to finish the evening chores then walk

over or hitch up the team to the wagon and ride over to visit a neighbor.

While the grownups visited, the children played action games like "Drop the

Hankerchief, or Three Deep, or Hide and Seek." The Children whooped and

yelled and ran until it was too dark to see then went inside and played

quite games like "Hide The Thimble", or just sat and listened to the talk.