Clark Co., Wisconsin Civil War

*********************************************************************************

Artifacts & Weapons from the Civil War

[Clark Co., WI Home] [ Veteran's Library Home]

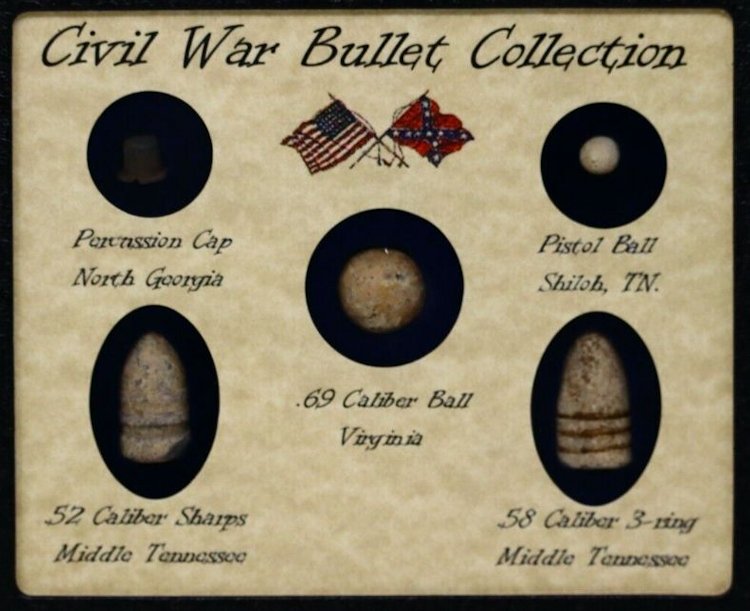

Bullet Collection

(Pictured above--Shot bullet from the battle of Gettysburg)

[Enlarge]

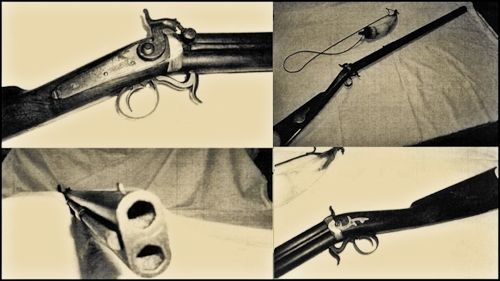

Rossmans Civil War Musket

[Enlarge]

[Clark Co., WI Home] [ Veteran's Library Home]

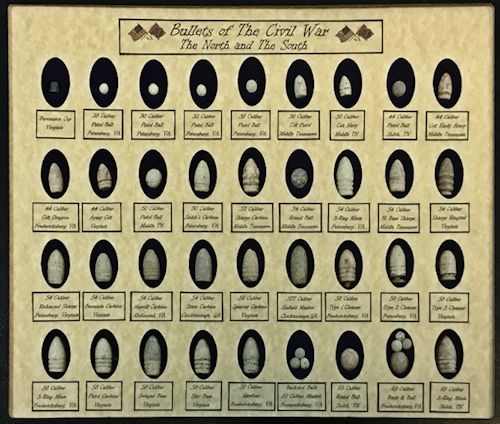

Confederate Canister Shot & 3-Ring Miniballs recovered in Appomattox VA

[Enlarge]

The First Car Phone Was The Civil War

Telegraph Wagon

This Information appeared in our Sept., 2023 Anagram

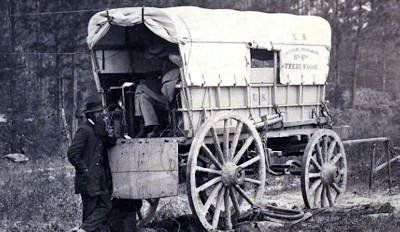

A TELEGRAPH BATTERY-WAGON

NEAR PETERSBURG, JUNE 1864

The operator in this photo is receiving a telegraphic message, writing at his

little table in the wagon as the machine clicks off. Each battery-wagon was

equipped with such an operator's table and attached instruments. A portable

battery of one hundred cells furnished the electric current. No feature of the

Army of the Potomac contributed more to its success than the field telegraph.

Guided by its young chief A.H. Caldwell, its lines bound the corps together like

a perfect nervous system, and kept the great controlling head in touch with all

its parts. Not until Grant cut loose from Washington and started from Brandy

Station for Richmond was its full power tested. Two operators and a few

orderlies accompanied each wagon, and the army crossed the Rapidan with the

telegraph line going up at the rate of two miles an hour. At no time after that

did any corps lose direct communication with the commanding general. At

Spotsylvania the Second Corps, at sundown, swung round from the extreme right in

the rear of the main body to the left. Ewell saw the movement, and advanced

toward the exposed position; but the telegraph signaled the danger, and troops

on the double-quick covered the gap before the alert Confederate general could

assault the Union lines. THE MILITARY~TELEGRAPH SERVICE, By A. W.

GREELY

Major-General, United States Army

*****************************************

The actual vehicles that are the ancestors of all our on-line cars were called

Telegraph Battery Wagons. Just like the cell phone of today, most of the

internal volume was consumed by battery needs. Open your cell phone and you'll

find that most of the interior is packed with a form-fitting rechargeable

battery. Open one of these telegraph wagons, and you'll find the same thing is

true, essentially. Almost all of the wagon was packed with batteries.

Now, keep in mind these aren't the nice, clean, not-scar-you-with-acids

batteries we enjoy today. These were likely something closer to a crapload of

acid-filled jars. Common telegraph batteries of the era were Daniell Cells,

which were, too keep things exciting in a moving wagon, open-topped jars.

Closed-jar lead-acid Leclanché batteries, one of the first rechargable battery

cells, didn't come around until after the war in 1866.

These Daniell Cell batteries made about 1.1 V each, and the number of batteries

needed to send a signal a given distance varied on the type of wire it was

sending over. Some estimates give 2V per 20 miles, some much more. Even if we

estimate 1V per 10 miles, that's a lot of bulky, leaky batteries to get a useful

distance. An average load of batteries for a telegraph battery wagon seems to

have been about 100 cells.

In addition to being packed with battery cells, these wagons also had a small

area with a telegraph key and a place for a person, very often a civilian

contractor, to operate it. This is the key part that makes these clunky wagons

so significant. Telegraphs were the first commercial/mainstream use of anything

electrical at all, and the placement of a telegraph set in a wagon makes this

combination the first electric component in any vehicle, ever. Unless someone

finds evidence of a mobile electroplating setup in an ancient Persian chariot,

at least.

Since I'm already pretty wildly diverging from our usual motor-driven fare, I

may as well keep going, because there's some interesting stuff here. These

mobile telegraph wagons would link one another with miles and miles of wire, and

then at other points link into the larger established telegraph network. This

would allow both inter-camp instant communication and also communication with

Washington (or a bit less commonly, Richmond).

Since telegraphs use just one wire with simple coded pulses sent over them, it

was very easy to connect these lines — when you have only one wire to connect,

it's tricky to get it wrong. That also means the Civil was was the birth of the

first cyberwarfare, cyberespionage, and hacking. I'm taking some liberties on

the use of "cyber" but you can argue that a virtual electrical, Morse-coded

world was made by the telegraph network, and that's roughly analogous to the

internet.

Hacking/eavesdropping lines was pretty easy. You'd send some soldier/telegrapher

out to a quiet section of telegraph line, and they'd splice in their own wire

linking to their own telegraph sounder. That's it. To help combat this, the

Union and Confederate armies used two tactics: shoot anyone they saw doing this,

and codes.

These codes are especially interesting. According to the Civil War Signals site,

an effective Union cipher was to use nonsense words mixed in the real message,

and key words would signal a matrix layout for the words, and the order the

words were to be read and/or ignored. The resulting encoded messages sound like

hilarious dada-poetry:

Washington, D.C.,July 15,1863

A.H. Caldwell, Cipher-operator, General Mead's Headquarters:

Blonde bless of who no optic to get an impression I madison-square Brown cammer

Toby ax the have turnip me Harry bitch rustle silk adrian counsel locust you

another only of children serenade flea Knox country for wood that awl ties get

hound who was war him suicide on for was please village large bat Bunyan give

sigh incubus heavy Norris on trammeled cat knit striven without Madrid quail

upright martyr Stewart man much bear since ass skeleton tell the oppressing

Tyler monkey.

Bates.

Except from Jason Torchinsky, 18 Jan 2013