Clark County, Wisconsin History

Tecumseh and the War for the Northwest Territory

by David DeWitt, Wisconsin Examiner @ istock

Tecumseh came of age amidst the

French and Indian War, and in 1774, at the Battle of Point Pleasant during Lord

Dunmore’s War removing the Shawnee from Kentucky, his father was killed.

By all accounts athletic, smart, dutiful, and charismatic, Tecumseh vowed to

become a warrior like his father and joined the native confederacy under Mohawk

Chief Joseph Brant.

By the end of the Revolutionary War, many native peoples had been pushed out of

the eastern portion of Ohio, but remained in the central and western portions,

including the Shawnee and Tecumseh.

Tecumseh led raids on American boats making their way down the Ohio River, and

later, in 1791, he further established himself at the Battle of the Wabash near

Fort Recovery, Ohio, a crushing defeat of General Arthur St. Clair that forced

St. Clair to resign.

The native confederacy suffered a crushing defeat of their own in 1794 at the

Battle of Fallen Timbers along the Maumee near Toledo. After the battle, about

250 warriors stayed with Tecumseh and followed him to what would become

Prophetstown, near the confluence of the Tippecanoe River and the Wabash River,

now commemorated as Prophetstown State Park in West Lafayette, Indiana.

|

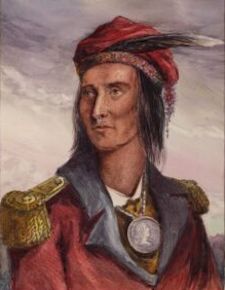

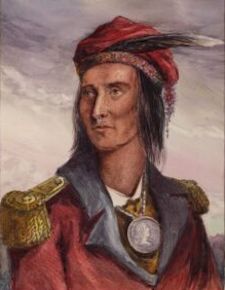

Tenskwatawa by Charles Bird King |

In May 1805, Lenape Chief Buckongahelas, one of the most important native leaders in the region, died of either smallpox or influenza. The surrounding tribes believed his death was caused by a form of witchcraft, and a witch-hunt ensued, leading to the death of several suspected Lenape witches. The witch-hunts inspired a nativist religious revival led by Tecumseh's brother Tenskwatawa ("The Prophet"), who emerged in 1805 as a leader among the witch hunters. He quickly posed a threat to the influence of the accommodationist chiefs, to whom Buckongahelas had belonged. As part of his religious teachings, Tenskwatawa urged Indians to reject European American ways, such as liquor, European-style clothing, and firearms. He also called for the tribes to refrain from ceding any more lands to the United States. |

“The Prophet” of Prophetstown was not Tecumseh, but his brother Tenskwatawa.

Ohio became the 17th state with a Feb. 19, 1803 act of Congress. (Statehood is

celebrated on March 1 because March 1, 1803, was when the Ohio legislature met

for the first time in the then-capital, Chillicothe.)

In 1808, Tecumseh and Tenskwatawa began assembling a large, multi-tribal band of

followers under a message of resistance to settlers, the American government,

and assimilation.

While Tenskwatawa took up the role of “Prophet” spiritual leader predicting a

new Indigenous nation, Tecumseh served as ambassador, traveling up to Canada, as

well as down south to areas such as Alabama to recruit tribes to join their

confederacy of native peoples.

William Henry Harrison

Portrait of William Henry Harrison, from The White House.

Meanwhile, Indiana Territory Gov. William Henry Harrison was organizing American

forces to put down the Indigenous resistance to settlement. He made a series of

treaties with various tribes capturing Indiana territory, and in 1809, Harrison

signed the Treaty of Fort Wayne with the Delaware, Miami, Kickapoo and others,

but not the Shawnee. In it, he took large swaths of native territory and spurred

Tecumseh and Tenskwatawa to double-down on their efforts. Tecumseh urged other

tribes to flout the treaty and join his resistance at Prophetstown. As he was

amassing forces, he avoided direct conflict with the United States, attempting

to build his strength first.

In 1810, Tecumseh met with Harrison at Harrison’s Vincennes, Indiana, home

Grouseland (The Vincennes and Grouseland treaties are others Harrison signed to

capture Indiana territory land). Tecumseh offered loyalty to America if the Fort

Wayne Treaty lands were returned. If they were not, Tecumseh told Harrison he

would seek alliance with the British, with whom he had been reluctant to ally as

he saw the British as using native forces on the frontier for their own ends.

Harrison scoffed at the idea of common native ownership of lands, asserting that

the U.S. had separate treaties with separate tribes for separate lands.

After the meeting, rebuffed, Tecumseh continued building alliances with other

native tribes. Harrison meanwhile began appealing to Washington, D.C., to launch

an all-out war against the native confederacy. In the summer of 1811, Harrison

and Tecumseh met again, at Harrison’s request. That meeting was as unproductive

as their first, and Tecumseh told Harrison, and later Tenskwatawa, that he would

be travelling and wanted “no mischief” while he was away, so that when he

returned they could resume negotiation over the disputed lands.

Battle of Tippecanoe

Portrait of Tenskwatawa from the National Park Service.

Harrison received word from U.S. Secretary of War William Eustis that peace

should be preserved unless Tenskwatawa attacked. Harrison then sent Tenskwatawa

a series of letters making demands. He accused the Shawnee of murder and

stealing horses, and ordered non-Shawnee residents out of Prophetstown.

Tenskwatawa only offered to return horses. Harrison began to assemble an army of

soldiers, gathering about 1,000.

While they were camping outside Fort Harrison, a guard was shot, and Harrison

considered this an act of aggression giving him cause to come down hard on

Prophetstown, writing to Eustice of Tenskwatawa, “Nothing now remains but to

chastise him.”

Harrison’s forces approached Prophetstown on Nov. 6, 1811, and camped on

Burnett’s Creek. What happened next is murky. A Kickapoo chief said that the

shooting of two Winnebago warriors by sentries aroused the indignation of the

people of Prophetstown, while Tenskwatawa himself in 1816 blamed Winnebago

warriors for launching an attack on Harrison’s camp.

Regardless of how it began, during a night council meeting Nov. 6 Tenskwatawa

seems to have agreed to a preemptive strike, and is said to have offered to cast

spells to prevent native warriors from being harmed. In the pre-dawn hours of

Nov. 7, 1811, Harrison’s sentinels encountered advancing native warriors, and

the Battle of Tippecanoe began. The Indigenous efforts were scattershot and

disorganized, and after about two and half hours, they retreated to Prophetstown

and confronted Tenskwatawa, who offered to cast new protection spells and

encouraged another attack.

His fellows did not take him up on that, and Prophetstown was abandoned

overnight. On Nov. 8, Harrison rolled into Prophetstown with his forces and

burned it to the ground. This was a severe blow to the native confederacy, and

launched Harrison into national fame. In 1840, Harrison ran for president and

won with running mate John Tyler under the slogan, “Tippecanoe and Tyler too.”

Tecumseh was reportedly furious with Tenskwatawa for losing the battle and

making the attack in the first place. Prophetstown was partially rebuilt, but

violence increased on the frontier after the battle.

As ambassador, Tecumseh told many tribes he visited of a sign that would come

telling them it was time to fight.

Many took a series of earthquakes in the South and Midwest in December 1811 —

known as the New Madrid earthquakes, which are the biggest in American history —

as that sign.

More violence ensued.

War of 1812

On June 1, 1812, at President James Madison’s request, Congress declared war on

Great Britain. This had to do with disputes over territorial expansion,

especially in the Northwest Territory, and Britain’s restriction of trade with

France and impressment of American citizens as British subjects.

Native peoples were split, but Tecumseh and his confederacy sided with the

British. The Surrender of Detroit, by J.C.H. Forster, from Wikipedia

Assigned to take over the city of Detroit, the siege was a success in large part

due to Tecumseh’s military thinking and strategy. A similar siege of Fort Meigs

failed, however, and morale waned.

In the fall of 1813 as conditions around Detroit worsened, the British began to

retreat east, but Tecumseh requested arms to stay in the Northwest Territory and

continue to defend native lands.

The British agreed to make a stand in Ontario near the northern shore of Lake

Erie, but communication broke down and so did the unity of forces, with some

defecting, some staying, and others continuing to travel east.

When Americans attacked, about 500 native confederate warriors including

Tecumseh were left to try to hold back 3,000 American soldiers. Tecumseh was

killed in the battle. Nobody knows exactly how, or what happened to his remains.

The death of Tecumseh largely dismantled the confederacy of tribes he had

established, and their alliances broke down. The removal of Indigenous peoples

from the Upper Midwest then continued apace, and Tecumseh’s dream of a Native

American nation evaporated. In Ohio, obviously, we are living where it would

have been.

Sculpture of dying Shawnee chief Tecumseh by Ferdinand Pettrich.

Photo from the National Portrait Gallery.

|

© Every submission is protected by the Digital Millennium Copyright Act of 1998.

Show your appreciation of this freely provided information by not copying it to any other site without our permission.

Become a Clark County History Buff

|

|

A site created and

maintained by the Clark County History Buffs

Webmasters: Leon Konieczny, Tanya Paschke, Janet & Stan Schwarze, James W. Sternitzky,

|