It was early September 1959, and the school year was already a week old. The hot, humid, lingering summer sun glared into my eyes as I squinted toward the waving hand of my school teacher. She stood poised on the steps of the one-room schoolhouse like an alert watchdog. Suddenly, a strong gust of prairie wind blew her skirt up over her shoulders. Suspended there, she resembled an upside-down umbrella. My blush turned to a smile as she fought the wind in order to regain her modesty.

I rose slowly from the grass and brushed pieces of dried stems from my pants as I sauntered toward the school's bell tower. It was a large old bell, bigger than any I'd ever seen, and the tower rose higher than the schoolhouse roof.

It was my turn to ring the bell, signalling the end of noon recess. As I pulled on its long rope, the bell swung like a pendulum and rang loud and echoed far down the valley. My hands clung tight to the swinging bell's rope as it lifted my eight-year old body nearly half as high as the tower. I realized that within a few minutes, our teacher would be reading passages from Laura Ingalls Wilder's Little House on the Prairie, as we kids listened to the story while resting our heads on our desks.

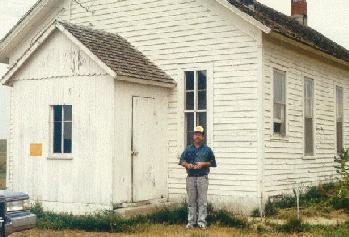

A sort of camaraderie existed in my one-room school that was as solid as the building itself. We were like a family. Built of clapboard siding around the turn of the century, School District #17, located near Wisner, Nebraska, had already served as the educational home for hundreds of rural youngsters.

But, the use of my school and others like it was not limited to education. Until the early 1900s or so, one-room schoolhouses were often the center of rural life. I still recall how ours was used for annual year-end picnics for all the families in the school district. It was used for school board meetings, and at election time it was a polling place.

Some rural schools were also used as community centers where groups such as 4-H, or a card or quilting club would meet. On the prairie, early settlers used the schoolhouse as a shelter from Indians. Often, a school teacher's contract required that he or she hold at least two or more special programs a year, usually around Christmas and then in the spring.Social gatherings in some schools included dances, concerts, musicals, ice cream and box lunch socials. Other uses included political events, church services, weddings and funerals.

The materials for construction of rural one-room schools were as varied as their uses. Usually, their proximity to local building materials dictated what was used. For example, many schools in the eastern U.S. were made of stone and brick. However, on the prairies of Kansas, Nebraska and the Dakotas, many early schools were made of sod, while others were nothing more than a hole dug into the side of a hill. In a few instances, early schools were made of logs, while canvas tents served some students.

At the turn of the century it was estimated that around 200,000 one-room schools existed in the U.S. Back then, and it's still the case today, Nebraska had the most one-room schools. Today, after years of efforts at consolidation, there are still over 400 single-teacher, one-room schools.

Changing educational standards, the movement of people from rural to urban areas, and the effect of recent state law, have all contributed to the declining number of one-room schools in both Nebraska and the nation.

In 1989, Nebraska passed legislation requiring Class 1 school districts to affiliate or merge with districts offering a K-12 curriculum by February 1993. If merged, the Class 1 district would close and send its students to the K-12 school. If the Class 1 district chose affiliation, it could remain open. However, in either case, tax levies would be the same for everyone. Thus, a smaller Class 1 district could find itself paying a higher tax levy than it had previously.

The era of the one-room school is becoming a thing of the past. For almost a century and a quarter, it served its purpose. But, time has a habit of out-growing everything. My old school closed its doors in 1992 after having only three students its previous year.

On Sept. 1, 1992, the school and all its equipment were auctioned off. It was a touching, reminiscent gathering as the auctioneer barked out the bids on old books, desks and other memorabilia. To the numerous former students, parents, school board members, teachers and friends who bid more than they wanted to on a piece of their past, it became a moving experience tinged with sadness in the knowledge that something important would be no more.

Two weeks later, we former students and teachers of School District #17 gathered for one last picnic at the Wisner City Park. The food was delicious and plentiful. Then we drove out to the old school for a last look and photographs. The building was empty... the black boards gone. So too was the picture of George Washington and chart depicting the cursive alphabet. The teacher's desk and her hand-held bell were also gone, along with that dog-eared copy of "Little House on the Prairie."

In reality, though, the rural one-room schools will never become completely extinct. I will often recall the figure of my teacher, with her dress flapping in the breeze. And I'll recall how my own father walked five miles to school on cold, snowy days. And in that memory, I'll feel once again both embarrassed and amused; or feel the chill my dad felt in that by-gone time when youngsters walked to school.

Every now and then, in a day dream, my teacher will stop me on the street and ask me to recite the alphabet, or do my multiplication tables.

And when someone on the street stares at me when I say out loud, "four times four is sixteen," I know there's a one-room school teacher somewhere who smiles and says, "That's a good job, Jimmy."